Generous Guests: Undocumented Immigrants Subsidize Our Health Care

Donald Trump's Health Care Policies, Part 1

It’s election season. Party conventions have passed. A debate looms Tuesday. Time to dig into the health care proposals of the candidates for the White House and the parties that back them, and maybe offer a little new data to debunk politicians’ lies and misdirections.

Good luck with that.

It has been a particular challenge this year to get an accurate fix on what the major party candidates say they stand for, never mind what they’ll actually try to do. The GOP candidate is notoriously inconsistent in his public statements and faces internal party dissent in the form of a widely publicized think tank report from his party’s allies that conflicts with some of his positions. His top “health care” priority - mass deportation to stop “millions of illegal immigrants” from driving up health care costs - is based on an inversion of reality, and Healing and Stealing has exclusive numbers to show it.

Meanwhile, the former Democratic candidate hadn’t published any agenda by the time of his disastrous debate performance and then blurted out a series of ideas he’d rejected for years in a last ditch, failed effort to rally his party behind him. His replacement has her own complex history of waffling and has resisted until this week publishing proposals on most issues.

But no one reads Healing and Stealing for the whining about how difficult the work is, so start with former President Donald J. Trump and the Republicans.

Who Speaks for Donald Trump? Former President Trump is often criticized for not publishing lengthy position papers, but the Republican National Committee platform defines his health care agenda relatively clearly, if in short bullets. And it is his agenda, as this New York Times article makes clear. The RNC platform committee was hand-selected by the Trump campaign. The campaign confiscated members’ cell phones and electronics when the committe met at the Republican convention and passed the campaign’s draft platform without a single amendment.

Before the convention, Trump shared his plans in official campaign statements, tweets and op-eds by surrogates. Our analysis of the platform is backed up by the issues section of donaldjtrump.com, known as Agenda47, along with other statements, press releases and the candidate’s ever-shifting public statements (really, is this guy going to try to repeal Obamacare again or not?).

Whenever Democrats occupy the White House, the right wing of the corporate think tank/NGO complex publishes hundreds of pages of policies they expect a GOP President to enact. For 2024, the Heritage Foundation organized a coalition with more than 100 conservative organizations called the 2025 Presidential Transition Project, or Project 2025, which published a detailed policy agenda entitled “Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise.”

Whether or not your favored candidate actually wants to implement your policy proposals, the problem with publishing 920 pages of your plans for the country is that it inevitably includes some really unpopular ideas. Trump and his campaign have vehemently denied that Project 2025 represents his views. The GOP platform differs in several significant ways from the Project 2025 document.

However, Project 2025 was written by organizations that expect to place a significant number of people in a possible Trump Administration and the GOP platform and Trump’s statements sometimes include coded rhetoric echoing longstanding Republican health care policy proposals. Where appropriate, we’ll look at Project 2025 and other recent party documents, using Healing and Stealing’s Secret GOP Healthcare Decoder Ring as a guide to possible Trump Administration initiatives or as an illustration of tensions within conservative politics.

Trump’s health care proposals fall into seven categories. With the potential exception of pharmaceutical price controls, they amount to very little that will address the triple crises of cost, access and quality that afflict U.S. health care. This article focuses on the first two categories and part of the third, in part because it has taken some time to analyze new data on Trump’s claim that undocumented immigrants are driving up health care costs, presented here exclusively for Healing and Stealing readers. We’ll cover the others in a second article. Overall, former President Donald J. Trump promises to:

Reduce the cost of healthcare by deporting millions of “illegals” who are driving up costs, in part because they get or are about to get “free healthcare.” Trump blames Democrats’ Open Borders and resulting Migrant Invasion for rising health care costs that are destroying American families’ finances and bodies. The truth is the opposite - undocumented immigrants subsidize health care for everyone else and Healing and Stealing has the numbers.

Neither cut Medicare benefits nor raise the retirement age - a position that has forced the GOP policy apparatus to shift its rhetoric, although some coded platform language hints at backdoor cuts.

Do things that have already been done, some Trump did himself and some he claims he did but Biden actually did - most of which are supposed to address health care costs, none of which have yet restrained them and one of which hints that Trump may do what he says he won’t do.

Exercise federal power to control drug prices - Trump’s proposals go far beyond Biden’s policies, the most under-reported and misunderstood health care story in the campaign. It has important political ramifications beyond health care.

Maintain the Post-Dobbs abortion status quo - Trump insists abortion should be a state issue and explicitly rejects some of Project 2025’s extreme next steps, in particular supporting vitro fertilization.

Defund and criminalize health care for transgender people and their providers - Trump has a detailed list of policies to stop providers from helping people make gender transitions and to prohibit government employees from even acknowledging the possibility of gender transition.

End federal support for “vaccine mandates” - although it remains unclear whether he means only requirements for COVID-19 vaccines or includes all childhood immunizations.

Category I: Deport Millions of “Illegals” Who are Driving Up Health Care Costs

“Republicans will secure the Border, deport Illegal Aliens, and reverse the Democrats’ Open Borders Policies that have driven up the cost of Housing, Education, and Healthcare for American families.” -RNC 2024 Platform, p. 7

2. Strengthen Medicare. Republicans will protect Medicare’s finances from being financially crushed by the Democrat plan to add tens of millions of new illegal immigrants to the rolls of Medicare. RNC 2024 Platform p. 12.

The radical left communists hate you, and they hate our Middle Class. Under Biden's scheme, the benefits that will go to illegal aliens include food stamps, free healthcare, welfare checks, and a host of other programs the likes of which you would not even believe. -Agenda47: No Welfare for Illegal Aliens

Trump insists that millions of people he calls “illegals” are driving up health care costs and that Democrats have a plan to “add tens of millions of new illegal immigrants to the rolls of Medicare” and thereby bankrupt the program that helps Americans who are 65 years or older or disabled afford medical care.

The national Democratic party hasn’t endorsed such a plan. Nor have they proposed to give “millions” of “illegals" “free healthcare.” In fact, Trump’s premise that undocumented immigrants are driving up U.S. health care costs is not only false, it’s the opposite of reality: undocumented immigrants spend large portions of their income subsidizing health care for the rest of us, and certainly for elderly and disabled Americans.

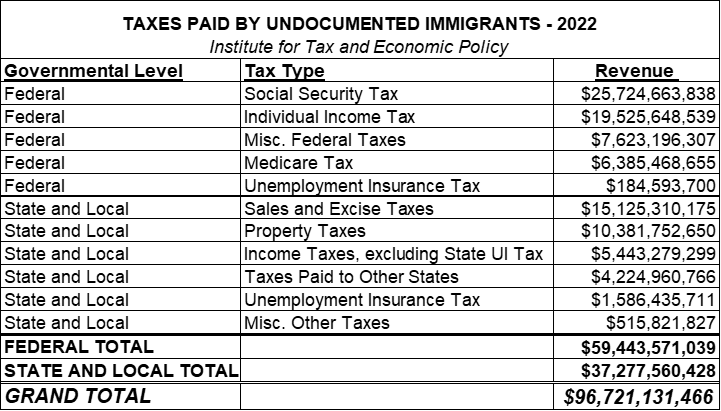

According to estimates by economists from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), undocumented immigrants paid $96.7 billion in federal, state and local taxes in 2022 - $59.4 billion to the federal government and $37.3 billion to state and local governments.

Undocumented taxpayers paid $27.5 billion in federal Social Security taxes and another $1.8 billion in federal and state unemployment taxes, which are designated for a single, non-health care purpose. We’ll ignore them and the spending they generate for the purpose of this analysis.

That leaves $62.8 billion in taxes, large portions of which are spent for various federal, state and local health care purposes.

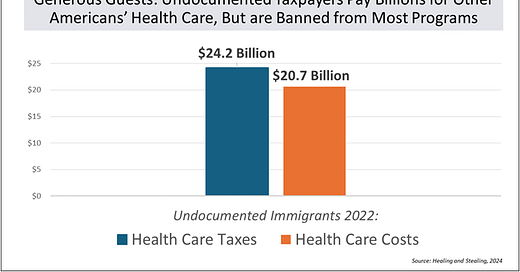

Based on the proportion of government funds spent on health care, Healing and Stealing estimates that undocumented taxpayers paid $24.2 billion in taxes to various governments for health insurance programs and health care delivery in 2022, much of which undocumented taxpayers are ineligible to receive. These taxes exceed the entire estimated cost of all health care for undocumented immigrants in the U.S. in 2022.

Using ITEP’s estimated tax payments as the basis, undocumented taxpayers’ share of government spending on health care includes:

FEDERAL ($17.2 Billion)

$6.4 billion in Medicare payroll taxes - mandatory federal payroll taxes set aside exclusively for the Medicare Part A Hospital Trust Fund.

$2.4 billion more for Medicare - Congress also funds Medicare with general revenues. Health care accounts for 40% of federal spending not funded by Social Security, unemployment insurance payroll taxes or the Medicare Trust Fund. $400.7 billion or 8.9% of general spending after removing Social Security and Medicare Trust Fund expenditures went to Medicare in 2022. 8.9% of the $27.1 billion of undocumented taxpayers’ federal non-payroll taxes is $2.4 billion.

$4.1 billion for Medicaid, CHIP and ACA subsidies - The federal share of the three means-tested health insurance programs accounts for $678.2 billion or 15.1% of general federal spending, meaning undocumented taxpayers paid $4.1 billion in federal taxes for these programs.

$1.2 billion for health care for federal workers, active military and veterans: The Federal Employee Health Benefits Program, Veterans Health Administration and Military Health System together cost $203.4 billion in 2022. When adjusted to avoid double counting the cost of health insurance and Medicare payroll taxes for civilian employees of government health care agencies,* the total is $191.2 billion, or 4.3% of non-payroll tax spending. Undocumented taxpayers’ share of health care for federal civilian workers, armed forces personnel and veterans was $1.2 billion.

$1.9 billion to subsidize Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance: The Congressional Budget Office estimates that federal tax breaks for private sector job-based insurance cost $316 billion in 2022, which we adjusted to $307.6 billion to avoid double counting the subsidy for federal, state and local government health care workers. That amounts to 6.9% of non-payroll tax spending, meaning $1.9 billion in undocumented taxpayers’ federal taxes subsidized private health insurance.

$1.2 billion for “other” health programs: Federal support for other health programs, including the Indian Health Service, cost $201.3 billion or 4.5% of non-payroll tax spending. Undocumented taxpayers contributed $1.2 billion.

STATE AND LOCAL: ($7 Billion)

$1.9 billion for Medicaid: When adjusted to remove the effect of federal payments to state and local governments and expenditures for unemployment benefits,* the state share of Medicaid spending accounts for 5.4% of total direct state and local government expenditures, including $1.9 billion of undocumented taxpayers’ money.

$1.4 billion for health care for state and local government workers: In their role as employers, state and local governments made payments for health insurance and Medicare payroll taxes for their employees accounting for 4.0% of total direct spending, funded by $1.44 billion in taxes from undocumented taxpayers.

$2.0 billion for State and Local Public Hospital Expenses: State and local governments operate roughly 15% of community hospitals in the U.S. The expenses for those hospitals account for 5.5% of spending, including $1.98 billion in taxes from undocumented taxpayers.

$1.7 billion for other health programs: State and local funding of other health programs accounts for 4.8% of spending, translating to $1.71 billion in taxes paid by undocumented taxpayers.

*Healing and Stealing adjusted the amounts for several categories to account for: double-counting health insurance costs for employees of health care programs; double-counting the value of tax subsidies for employer-sponsored health insurance for government employees, and; the amount of state and local government revenue that originates with the federal government. See “A Little Extra for the Data Curious” for methodology.

Most of the $24 billion that undocumented taxpayers paid various levels of government for health insurance and health care services is a gift to people with legal authorization to live in the U.S.

People living in the U.S. without legal authorization are ineligible for or have limited rights to use nearly all of the major public health insurance programs. They are barred from Medicare altogether and from federal, state and local government employment, active duty military service and, by the letter of the law, private employment, although some undocumented immigrants enroll in job-based health insurance.

All undocumented residents are entitled to “emergency Medicaid.” Under federal law, if someone shows up at the emergency room and can later prove they’re poor, Medicaid will pay for emergency care. In most states, however, Medicaid won’t enroll undocumented people for comprehensive coverage that pays for physician visits, non-emergency hospitalization, prescription drugs and lab tests.

That is changing slowly. States are allowed to enroll people in Medicaid or parallel state-funded programs regardless of immigration status, but only if coverage for people who don’t meet federal eligibility standards is paid for purely with state funds. As of June 2024, six states and the District of Columbia have various programs that allow enrollment of some categories of people in Medicaid or parallel state programs regardless of immigration status. California’s is the most extensive, now open to all poor people regardless of immigration status, although any funding for undocumented taxpayers and their families must come entirely from state-generated funds.

Like anyone else, people without legal authorization to live in the U.S. must prove they are poor enough to qualify for Medicaid, and keep doing so at least once a year. Even when they overcome the natural fear of engaging with government at all, they have faced the same struggles maintaining coverage during the Great Medicaid Purge as legally authorized foreign-born residents and U.S. citizens. And since undocumented taxpayers paid $4.5 billion in taxes to support Medicaid, it can hardly be described as “free,” especially since the government refuses to use the estimated $3.6 billion in their own federal taxes that go to Medicaid for their health care.

Given these circumstances, it’s not surprising that, according to surveys by the Kaiser Family Foundation and Los Angeles Times, half of all “likely undocumented” immigrants report being uninsured, a rate ten times that for citizens. This is especially troubling because undocumented taxpayers’ health care taxes - most of which subsidize health care for other people - were likely higher than the cost of health care for all undocumented people currently residing in the U.S. in 2022.

A December 2020 article by the University of Utah’s economics professor Fernando Wilson and colleagues found that health care for undocumented adults cost $1,880 per person in 2022 dollars. With an estimated 11 million people living in the U.S. without legal authorization, their health care would have cost $20.7 billion, $3.5 billion less than undocumented taxpayers paid various levels of government for health care, mostly for the rest of us. Indeed, since most of the publicly-financed health care that our taxes paid for is unavailable to undocumented taxpayers, it’s clear that we’re asking undocumented taxpayers to pay twice for their own health care.

The Democrats haven’t offered to give undocumented immigrants “free health care.” The closest thing to anyone getting free health care in the U.S. are proposals for improved fully-funded Medicare for All. 110 Democratic members of the House of Representatives are cosponsors of H.R. 3421, the Medicare for all Act of 2024, which would give everyone in the U.S. comprehensive coverage for all needed medical services without cost sharing. The Senate version has 15 cosponsors.

Some congressional supporters have said they intend to cover undocumented people, but for the moment, even the signature progressive universal health care proposal dodges the question. Both the House and Senate versions of the bill would cover all “residents” of the U.S., but leave it to the Secretary of Health and Human Services to establish the legal definition of a resident.

The Biden Administration’s lone federal expansion of health coverage for undocumented immigrants was a rule allowing people receiving Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) to enroll in ACA exchange coverage or in Basic Health Plans in states that have them. DACA refers to a series of Executive Orders dating to the Obama Administration that delay immigration decisions for a relatively small category of people who arrived in the U.S. as children without authorization years ago, allowing them to remain here temporarily. Congress has repeatedly failed to pass legislation known as the DREAM Act to permanently allow people covered by DACA — all of them now longtime U.S. residents known as “Dreamers” — to reside legally in the U.S.

This program isn’t “free” and doesn’t apply to anywhere near the “millions” of people Trump claims. Most people who buy Obamacare exchange insurance pay at least some portion of the premiums, as would any Dreamer. The Biden Administration’s fact sheet says the rule will help “more than 100,000” of the estimated 11 million people who were living in the U.S. without authorization in 2022. So maybe one percent of undocumented people, all of whom have lived in the U.S. for years, are now eligible for not-free healthcare.

Strategically and rhetorically, accusing millions of “illegals” of driving up Medicare costs marries two critical Trump campaign themes. Attacking and removing undocumented immigrants is the centerpiece of his entire campaign, including most health care issues. For example, emotional promises to end the scourge of drug addiction focus primarily on stopping the purported flow of Chinese fentanyl across the Mexican border.

Cleansing the body politic of the infection of violent, unwelcome, greedy criminals is the most tangible example of the restoration of American “greatness” Trump offers. That his rhetoric on Medicare and costs is an inverted mirror of the truth, that undocumented immigrants generously fund health care for the rest of us while being shut out of most of the benefits they pay for, seems not to matter to him or his party.

However, the opinions and votes of older American citizens matter greatly to the GOP. Promising to protect Medicare from a threatened bankruptcy caused by immigration is a tool to defend the major party whose rhetoric relies most explicitly on austerity from fears that Medicare’s increasingly threadbare benefits will be further cut or lost.

Category II: No Cuts or Eligibility Age Increase in Medicare

[W[e offer to the American people …the following twenty promises:

14. Fight for and protect Social Security and Medicare with no cuts, including no changes to the retirement age. - RNC Platform 2024, p. 4-5.

President Trump has made absolutely clear that he will not cut one penny from Medicare or Social Security. American Citizens work hard their whole lives, contributing to Social Security and Medicare. These programs are promises to our Seniors, ensuring they can live their golden years with dignity… RNC Platform 2024, p. 12.

Republicans have been skeptical of Medicare from the start. The 1965 law passed in one of the most lopsidedly Democratic Congresses in history. Senate Republicans split down the middle, while House Republicans voted unanimously against it in committee before a majority supported final passage.

Nearly 60 years later, Medicare is popular and the public opposes raising premiums or cutting benefits and eligibility. In polling last year, U.S. adults rejected increasing monthly Medicare premiums by 67%-10% and raising the Medicare eligibility age from 65 to 67 by 70% to 15%. Other surveys have found overwhelming majorities favor expanding Medicare to cover dental, vision and hearing care.

These attitudes pose a political problem for any Republican presidential candidate. For decades, one of the party’s core national messages has been that government spending is out of control and federal deficits and debt are causing personal financial problems for overtaxed Americans. Trump regularly promises to “slash” federal spending. With Medicare the second largest single federal expenditure, it’s hard to ignore when touting plans to cut government spending and taxes dramatically.

Trump is tackling the politics of Medicare head on with clear, simple, bumper-sticker promises that isolate Medicare (and Social Security) from his broader commitment to “slashing wasteful spending.” No cuts, no increase in the retirement age. Full stop.

He’s been consistent from the beginning of the campaign. In January 2023, as the new Republican House majority began debating how to reduce President Biden’s budget proposals, Trump released a video saying “under no circumstances should Republicans vote to cut a single penny from Medicare or Social Security to help pay for Joe Biden’s reckless spending spree.”

Trump attacked both of his leading Republican primary opponents - Florida Governor Ron DeSantis and former U.N. Ambassador and South Carolina governor Nikki Haley for supporting Medicare benefit cuts. On January 24, 2024, Trump criticized Haley for supporting a 2011 proposal by then-Speaker of the House Paul Ryan (R-IL) to transform Medicare into a voucher program:

Governor Haley Wanted To Gut Social Security And Medicare For South Carolinians And Even Defended The Paul Ryan Plan To Get Rid Of Medicare Entirely…

Haley defended the Paul Ryan budget plan of 2011 that would have transformed Medicare into a voucher/premium support system. Trump Campaign News Release 1/24/2024

National Republicans are tentatively following Trump’s lead on Medicare.

The House Republican Study Committee budget for fiscal year 2023, published before Trump urged the GOP not to “cut a single penny” from Medicare, proposed raising the Medicare eligibility age from 65 to 67. Raising the age is a longstanding goal for politicians who style themselves fiscal conservatives and the RSC’s budget represents the ideas of the most conservative wing of the House GOP. Yet after Trump challenged the wildly unpopular idea, raising the Medicare eligibility age disappeared from the RSC budget for fiscal years 2024 and 2025, and does not appear in Project 2025.

Almost no one in Washington from any party actually proposes “cutting” Medicare spending or directly reducing access to eligibility for the program. All policies, no matter how destructive, are framed as “protecting,” “saving” or “improving” Medicare. The Medicare chapter in the last three RSC budgets is called “Saving Medicare,” and along with Project 2025 repeats the usual terrifying alarms about the imminent “bankruptcy” of the Hospital Trust Fund, a meaningless accounting gimmick given how much of Medicare is already funded through general revenues.

Trump’s criticism of Haley’s support for a “voucher/premium support” approach to Medicare highlighted an interesting difference between his campaign and the Republican Party policy apparatus. The current Republican Study Committee budget explicitly calls for transforming Medicare into a “premium support” program, under which all Medicare funds would be placed into one pool of money. Then Medicare patients could choose either traditional Medicare or a Medicare Advantage plan, with the private and public programs in direct competition. The federal government would make a set contribution to those premiums.

Project 2025 plays it coy, proposing vaguely to give beneficiaries “direct control over how they spend their Medicare dollars” while omitting any detail and avoiding hot button phrases like “premium support.” But both the RSC budget proposal for the “premium support model” and the vaguer Project 2025 language include the recommendation that enrollment in a Medicare Advantage private health insurance plan should become the default option for initial enrollment of people newly eligible for Medicare, a recommendation repeated by Project 2025.

Even without moving to a full “premium-support” voucher model, defaulting to MA likely exacerbates a longstanding trend where Medicare patients with higher medical needs tend to choose to stay in traditional Medicare to make sure they can choose their doctors freely, which would put additional financial pressure on traditional Medicare. (MA default is an acceleration of longstanding bipartisan policies that have allowed escalating out of pocket costs to drive a majority of Medicare beneficiaries to sign up for private health plans. More detail when we take a look at Vice President Kamala Harris and the Democrats.)

Despite Trump’s criticism of his party’s policy apparatus, the GOP platform contains language pointing in the direction of further Medicare privatization even while claiming not to cut a penny. A future Trump White House would frame such policy proposals as increasing Medicare beneficiaries’ “choices” by allowing more “competition” among Medicare Advantage plans and between the private plans and the government, ostensibly without cutting benefits. Consistent with both the RSC budgets and Project 2025, the portion of Trump’s platform promising “Affordable Healthcare,” says Republicans “will increase Transparency, promote Competition, and expand access to new Affordable Healthcare and prescription drug options.”

Although Healing and Stealing has great faith in our GOP Policy Secret Decoder Ring, it’s impossible to predict a future Trump Administration’s Medicare policies (besides keeping the current prohibition on enrollment by undocumented immigrants). Should Trump win, Republicans are likely to “discover” the shocking news that the fiscal mess left by Biden is just so much worse than even they warned us. This typical exercise after a Democrat leaves office may prompt attempts to “save” Medicare with market competition.

On the other hand, the Trump campaign is behaving as if any proposals to cut Medicare are political poison. He has successfully enforced party discipline to his views by prompting both the House Republican Study Committee and Project 2025 to expunge eligibility age increases from their documents and ruthlessly ensured that the platform avoids any use of explicit “premium support” language. However, the next category includes an additional hint.

Category III: Promising Things that are More or Less Already Done

Medicare helps explain one of the stranger facets of former President Donald J. Trump’s health care proposals: his penchant for promising things that are pretty much already done. Some are things Trump did himself and others are things he claims he did, but that Biden really did. The first - price transparency - is relevant to the broader discussion of Medicare policy.

During the last two years of Trump’s first term, his administration drafted and finalized new detailed hospital and private insurance price transparency regulations.

To Trump’s credit, it was the first time anyone in Washington DC had done anything to pierce the veil of secrecy hiding the actual prices paid by insurers and patients for health care, and by employers for health plans. In fact, it was such a shocking development that I couldn’t persuade some colleagues in the labor movement that it was actually happening.

President Joe Biden went ahead and implemented the Trump regulations. Hospitals are now required to publish detailed information on prices by service by individual payer, and insurers are also required to publish both the premiums they charge and the prices they pay providers.

Many hospitals have resisted, either by just not publishing the data or by dumping it in big data files that are hard to understand if you don’t have enough computer skill or technical knowledge of how hospitals are paid and the labyrinthine coding systems they use. These dodges have generated outraged media attention, since the regulations explicitly require hospitals to reveal prices in a form patients can use to comparison shop without needing to be health care economists.

As a matter of principle, Healing and Stealing believes that if you’re going to bother publishing price data, you might as well do the work to make it understandable to ordinary people. Hospitals must be held accountable, and, well…

….whatever.

Frankly, dear reader, we don’t give a damn.

Personal consumer behavior will not suddenly impose market discipline on hospital spending, no matter how fancy hospitals’ pricing websites get. Prices are negotiated between insurers (or sometimes employers directly) and hospitals, and the terms of most patients’ health plans are set by negotiations between employers and insurers. Most patients choose most of their hospital care through a combination of where their doctors practice and which facilities are in their insurance network.

There are a few people with the expertise, money, personality and spare time to dig into prices, buck their physician’s desires and find a cheaper hospital. Good for them.

But expecting most people to do so is both unrealistic and cruel. Normal countries set uniform prices through national or regional rate-setting processes. Substituting individual “consumers” for that structure indulges in market fantasy and heaps more administrative work onto patients who already spend hundreds of millions of hours each year on the phone with their insurers trying to get their care paid for.

The employers, governments and giant health insurance corporations who actually buy health care now have the data they need to analyze markets and compare their own prices to relevant markets (actually, the insurers have always had it, but that’s for another day). It may take tweaks to data regulations to make it better, but if you’re willing to invest in computer and brain power, you should be much better equipped to understand your institution’s health care costs relative to other market participants than you were when Trump was first elected.

None of which stops Trump from promising to “increase fairness through price transparency.” On the surface it’s odd since his administration set in motion the first real price transparency system in U.S. health care history.

However, enhancing and empowering consumer choice by creating fully informed markets is not only standard boilerplate for Republican health care policy generally, but some form of it appears with nearly every mention of shifting Medicare benefits to the “premium support/voucher” structure that Trump publicly repudiates. Although Project 2025 avoids explicit mention of the words “premium support,” the standard language used to support such proposals - increasing Medicare patients’ control over their own spending through transparency - is one of four “goals and principles” for reforming Medicare:

Time will tell if Republicans’ strong commitment to doing what they’ve already done is code for doing what Trump says he won’t do.

Next: Trump Part 2 - Prescription drugs, fudging abortion, trans hatred, and vaccine freedom. For readers who lean Republican or find neither major party inspiring, rest assured there’s plenty to come on the Democrats and third party candidates.

A LITTLE EXTRA FOR THE DATA CURIOUS

I. Undocumented Taxpayers’ Health Spending:

Calculating how much of the taxes paid by undocumented taxpayers went to health care requires knowing: a) How much did undocumented people pay in taxes? b) How much of those tax payments are available for health care? and c) What percentage of the taxes available for health care spending are actually spent on health care?

No single source answers those questions in full and the questions are complicated by the fact that not all taxes go into one big pot to be distributed in easily identified proportions. Healing and Stealing relied on the following basic sources for this analysis - Congressional Budget Office publications on the federal budget and spending on health insurance subsidies; two tables from the National Health Expenditure files published by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS); U.S. census files on state and local government spending and employment; the Veterans Administration annual budget submission; annual Congressional Research Service reports on Military Health Services run by the U.S. Department of Defense; the U.S. Office of Personnel Management FedScope data warehouse on federal employment, and; Bureau of Labor Statistics and Commerce Department Bureau of Economic Affairs surveys of employment and compensation.

Any errors in this analysis are entirely Healing and Stealing’s responsibility. No other individual or organization had input on the development of the methodology or the analysis of the numbers. This includes the Institute for Tax and Economic Policy, whose only role beyond publishing their tax estimates was providing an excel file with a breakdown of the categories of taxation found in their report.

a) Undocumented Taxpayers’ Total Payments: Healing and Stealing obtained a breakdown of the Institute for Tax and Economic Policy’s estimates of taxes paid by undocumented immigrants in 2022, broken down in the following categories:

To begin the analysis, Healing and Stealing separated two types of taxes from more general revenue and spending.

Excluded Taxes: Federal Social Security taxes and federal, state and local unemployment insurance taxes are paid into segregated pools of money used exclusively for those purposes, most of which is spent on benefit payments. So we assume none of that money is for health care, and exclude taxes paid in those categories entirely from the analysis. We also subtract total Social Security spending from the “denominator” of our calculation of the percent of federal spending that goes to health care, and state and local expenditures for unemployment benefits from the state and local denominator. After excluding those taxes, our analysis of the ITEP tax payment estimates shows $69.2 billion available for potential spending on health care.

Medicare Taxes and Trust Fund Spending: Under the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA), 2.9% of all employees’ wages are paid to the federal government as taxes specifically for Medicare. The contributions are nominally split 50-50 between the employer and employee, at 1.45% each. The employer share is paid directly and only the employee’s 1.45% typically shows up on paychecks as a deduction. There’s no cap on the income that gets taxed - unlike Social Security - and high income earners (>$200,000 per year in 2024) pay an additional 0.9% on income above the threshold.

These taxes are earmarked specifically for the Medicare Part A Hospital Trust Fund. Healing and Stealing counts 100% of the $6.4 billion in Medicare taxes that ITEP identified from undocumented taxpayers as spent on health care. Along with the $6.4 billion in Medicare taxes, that leaves an additional $62.8 billion in taxes paid by undocumented taxpayers available for health care spending, $27.1 billion in federal tax payments and $35.7 billion in state and local tax payments. In calculating how much of these remaining taxes are spent on health care, we eliminated the portion of Medicare spending funded by payroll taxes from the denominator as well.

Percentage of Remaining Taxes Spent on Health Care: Healing and Stealing made separate estimates for federal and state and local spending.

FEDERAL

Denominator (total federal outlays): The Congressional Budget Office reported actual total federal outlays of $6.3 trillion in 2022 (CBO, “An Update to the Budget Outlook: 2023 to 2033”, 5/2023, Table 1). Healing and Stealing subtracted $1.2 trillion in Social Security outlays (CBO Update 5/2023, Supplemental Table 2), and, after accounting for 100% of undocumented taxpayers’ Medicare payroll taxes as health care spending, $574 billion in Medicare dedicated trust fund spending, leaving $4.5 trillion as the universe of possible health care spending.

Numerator (Federal Spending on Health Care): No single source comprehensively gathers all federal health care spending in one place. We started with the historical National Health Expenditures files for calendar years 1960-2022, published by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). They include tables for health spending for which the federal government is the “sponsor”, (Table 5.3) and state and local governments are the “sponsor” (Table 5.4).

The files may be downloaded as a Zip file with separate Excel or CSV files for each table here. The individual tables are clearly marked in the Zip folder. We relied on these tables as a baseline, but made adjustments based on calculations from other sources to ensure a comprehensive list (the NHE files omit certain health care spending), re-group various types of spending into different categories than those presented in the NHE federal “sponsor” spending, and to avoid double counting certain expenditures. Here are the detailed sources for determining the percentage of overall federal spending accounted for by each federal category in the article:

More for Medicare - $400.7 billion. We summed two lines for 2022 from NHE Table 5.3: “Federal General Revenue and Medicare Net Trust Fund Expenditures” at $400.1 billion, and; “Retiree Drug Subsidy Payments to Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance Plans” at $0.6 billion. The Retiree Drug Subsidy is an option under Medicare to allow employers and unions to continue offering drug coverage to retirees. $400.7 billion/$4.5 trillion = 8.9% (Rounding may make the percentage calculations seem off. See the attached excel file for details).

Medicaid, CHIP and ACA subsidies - $678.2 billion. The NHE reports these programs in four separate places. First we summed three lines: “Federal Portion of Medicaid Payments” ($569.7 billion); “Federal Portion of Medicare Buy-in Premiums” ($17.4 billion) and “Marketplace Tax Credits and Subsidies” ($74.1 billion). The Buy-in program helps states pay Medicare premiums for people who are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid, so we include it in this category as part of Medicaid spending. However, the NHE lumps Childrens Health Insurance Program spending into a large “Other Health Insurance and Programs” category. We obtained 2022 actual federal CHIP spending from “CBO’s May 2023 Projections for Net Federal Subsidies for Health Insurance Coverage for People Under Age 65”, Table 2 ($17.0 billion). CBO’s budget projection documents may be found here. $678.2 billion/$4.5 trillion = 15.1%.

Health care for federal workers, active military and veterans - $191.2 billion. The federal government is responsible as an employer for providing health coverage to its civilian and military workforce and to veterans of the armed forces. NHE itemizes the Federal Employee Health Benefits Program ($41.5 billion) and the federal government’s payment of Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund payroll taxes in its role as a civilian employer ($5.1 billion). However Table 5.3 lumps the Veterans Health Administration and Military Health System together in the “Other” category. We obtained the actual 2022 cost of Veterans health care from the Veterans Administration’s FY 2024 Budget Submission ($101.1 billion). The Military Health System doesn’t appear as a single budgetary item, but the Congressional Research Service publishes an annual consolidated summary “Budget Request for the Military Health System” report. Actual 2022 spending can be found in the FY 2023 version, Table 1 ($55.7 billion).

Since labor costs for civilian employees are included in topline budget numbers for programs like Medicare or VA Health, a portion of the NHE figures for health benefits and Medicare payroll taxes paid for federal civilian employees is counted twice. Using data from the federal Office of Personnel Management’s FedScope data warehouse, Healing and Stealing estimates that 26.1% of federal civilian employees are employed in health care programs catalogued in the NHE files. We multiplied the $46.6 billion in combined spending on health benefits and Medicare payroll taxes for civilian employees by (1-.261) to yield adjusted figures of $30.7 billion in payments for health insurance and $3.77 billion for Medicare payroll taxes, reducing the total to $191.2 billion. $191.2 billion/$4.5 trillion = 4.3%

Subsidies for Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance - $ 307.6 billion. The NHE table containing federal sponsored health spending does not include lost revenue from federal tax exemptions for private sector job-based health insurance. The closest estimate for 2022 is from the Congressional Budget Office “Federal Subsidies for Health Insurance Coverage for People Under Age 65: CBO and JCT’s May 2022 Baseline Projections, May 2022”, Table 2, pdf here; excel here.

Government employers and employees receive the same tax subsidies as private sector enterprises. Labor costs are included in the NHE program estimates. To avoid double counting subsidies for federal, state and local governments’ purchase of health insurance for their civilian employees, Healing and Stealing obtained data from The U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of Economic Analysis tables of employment by industry. According to the BEA data, federal civilian employees accounted for 1.6% of full time equivalent civilian employees in the U.S. and state and local government employees accounted for 11.4%.

FedScope data show 26.1% of federal civilian employees working for relevant health care agencies and programs, so we multiplied $316 billion*(1.6%*26.1%) yielding $1.32 billion in double-counted spending. For state and local employees we do not have detailed enough employment data in summary form analogous to FedScope, but instead use the percentage of state and local government spending devoted to health care as a proxy for employment (19.74%, see below). We multiplied $316 billion*(.114*.1974), yielding an additional $7.1 billion in double counted spending, for a total of $8.4 billion subtracted from the national total subsidies. $307.6 billion/$4.5 trillion = 6.9%.

“Other federal health insurance and programs” - $201.3 billion. The CMS National Health Expenditures files report $375.1 billion in 2022 outlays for “Other Federal Health Insurance and Programs.” As noted, Healing and Stealing subtracted VA ($101.1 billion), Military Health ($55.7 billion) and CHIP spending ($17 billion) from the category, leaving $201.3 billion. $201.3 billion/$4.5 trillion = 4.5%. NOTE: The remaining spending includes:

“maternal and child health, vocational rehabilitation, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Indian Health Service, federal workers’ compensation, other federal programs, public health activities, and investment (research, structures and equipment). Also includes government subsidy payments for COBRA coverage for 2009-2011, small business tax credits beginning in 2010, Early Retirement Reinsurance Program (ERRP) payments for 2010-2011, and payments for the Basic Health Program beginning in 2015. Excludes premiums paid for the Pre-existing Condition Insurance Program (PCIP) for 2010-2014.”

TOTAL FEDERAL: $1.779 trillion/$4.487 trillion = 39.6%

STATE AND LOCAL

Calculating the percentage of total spending by state and local governments on health care is complicated by the fact that state and local governments receive significant federal revenue. To avoid inflating the numbers, federal spending needs to be backed out of both total spending and estimated health care spending.

Denominator - Total Direct State and Local Government Spending: The best single source for overall spending by state and local jurisdictions is the Census Annual Surveys of State and Local Government Finances. As of publication, the summary 2022 survey data for local jurisdictions was not yet available. However, since the goal of this portion of the analysis is to determine the percentage of state and local government spending that goes to health care as opposed to specific expenditures in 2022, we use the complete 2021 data with the assumption that the overall percentages would not show extreme differences for 2022. In 2021, State and Local governments made $4.51 trillion in direct expenditures. They received a net $1.12 trillion in revenue through intergovernmental transfers from the federal government, which leaves $3.39 trillion. We then subtracted $177 billion in unemployment benefits, leaving $3.21 trillion in total expenditures originating from state and local revenue sources.

Numerator - Total State and Local Government Health Care Spending. As with federal spending, no single source captures the entirety of state and local government spending on health care. NHE Table 5.4 forms the basis for much of the estimates, but we make significant adjustments drawing on several other sources, notably the U.S. Census Bureau’s Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances and Annual Survey of Public Employment and Payroll (ASPEP). We also rely on the Bureau of Labor Statistics surveys of employer compensation spending (ECEC) for the percentage of total compensation of public employees spent on health insurance and Medicare taxes.

The State and Local analysis carries significant risk of either overestimating or underestimating health care spending. First, much of the federal money flowing to state and local governments is targeted specifically for health care, so failing to subtract out federal funding for state and local government operations would double count large amounts of spending. To match the adjustments to the denominator, Healing and Stealing multiplied all line items by 1- (revenue from the federal government/total direct spending):

Total Direct Expenditures = $4,505,661,168,000

Intergovernmental Revenue from Federal Government = $1,120,200,979,000

Unemployment expenditures = $176,945,449,000

Adjustment factor: 1-(($1,120,200,979,000+$1,120,200,979,000)/$4,505,661,168,000) = 0.712107417838571)

Second, as with federal spending, NHE spending figures for sponsor categories include the cost of labor by state and local government employees to administer programs or deliver services directly to the public. NHE Table 5.4 estimates expenditures by state and local governments on the costs of employer-sponsored health insurance and Medicare taxes paid by these governments in their role as employers. However, that spending may be double counted when the NHE figures for employee health insurance and Medicare taxes are added to other calculations of spending on specific programs and categories to reach a total. We’ve estimated the cost of employer-sponsored health insurance and Medicare taxes for workers employed in various state and local government-sponsored health care programs and subtracted that money from the NHE’s estimated totals for all government employees. The methodology is described in the “Health care and Medicare taxes for state and local government employees” section below.

Medicaid - $172 billion. NHE Table 5.4 shows 2021 spending of $221.4 billion for “State Portion of Medicaid Payments,” and $7.5 for the “State Portion of Medicare Buy-in Premiums,” for a total of $228.9 billion in Medicaid spending by state and local jurisdictions. That number explicitly excludes federal spending, and represents only the “state share” of spending. Since the federal share of Medicaid is a disproportionately large percentage of total federal transfers to states, there’s a surface logic in attempting to account for the entire $228.9 billion as “health care spending.” However, unlike federal Medicare payroll taxes, there is no specific “Medicaid tax” applied to undocumented taxpayers that is easily segregated, so we include Medicaid spending with general expenditures which are adjusted with a proportionate factor to remove federal spending. After adjusting the total to remove federal revenues, $172 billion/$3.21 trillion = 5.4%.

Health insurance and Medicare taxes for state and local government workers - $129.6 billion. NHE Table 5.4 reports $198.1 in combined state and local government payments for health insurance for state and local employees ($181.8 billion) and Medicare taxes for those workers ($16.3 billion). After adjusting to remove prorated federal revenues ($45.2 billion ESHI; $4.1 billion payroll taxes), the total is $148.8 billion.

Healing and Stealing estimates that $19.1 billion of total state and local government expenditures on health insurance and Medicare payroll taxes is for state and local employees working in health benefits and delivery programs ($17.6 billion for health insurance and $1.5 billion for Medicare payroll taxes). To prevent possible double counting, we’ve subtracted that amount from the NHE total, leaving $129.8 billion (rounding makes the subtraction seem inaccurate, see excel file for precise numbers) $129.8 billion/$3.21 trillion = 4.05%.

These additional adjustments require two distinct methodologies. The 2021 ASPEP reports 1,491,773 state and local government Full Time Employee Equivalents working in either the “Health” government function (464,133) or the “Hospital” government function (1,027,640), comprising 9.1% of the total of 16,391,418 state and local government FTEs in the survey. As a first step, Healing and Stealing multiplied the NHE’s figures for state and local health insurance and Medicare tax cost by (1-.091), leading to a subtraction of $18 billion.

According to the Census Classification Manual, workers who administer means-tested health care programs are not counted as part of the “health” function of state and local governments in the ASPEP, but rather included as part of a much broader “Public Welfare” spending function, from which it is difficult to extract health care workers specifically.

We do however, know how much Medicaid, by far the largest such program, spends on administration - 5% of total costs. To avoid double counting for spending on health care-related public welfare employees, Healing and Stealing first assumed the entire administrative costs for Medicaid are labor costs (although they likely are not). The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ September 2021 Employer Costs for Employee Compensation survey reported that state and local governments spent an average of 11.2% of compensation on health insurance. Multiplying 5% of the full cost of state and local governments’ contributions to Medicaid by 11.2% yields another $1.2 billion to deduct, where:

($221.4 billion*.05)*.112 = $1,244,028

The same process was repeated for Medicare payroll taxes, yielding $8 million to subtract, where:

($7.5 billion*.05)*.01 = $8,230,812

Altogether, estimates for the cost of health insurance and Medicare payroll taxes for state and local hospital, health and Medicaid public welfare workers reduced the NHE total estimates for these categories by $19.1 billion.

State and Local Public Hospital Expenses - $178 billion. State and local governments operate roughly 15% of community hospitals in the U.S., according to the American Medical Association. The Census of State and Local Government Finances summary for 2021 reported $236.9 billion in expenditures for those hospitals. Subtracting the portion accounted for by revenues received from the federal government leaves $178 billion. $178 billion/$3.21 trillion = 5.5%.

Other health programs- $154 billion. NHE table 5.4 reports $204.9 billion in state and local funding of “other” health programs. Note that for Healing and Stealing’s estimates, this category differs from the federal “Other” category in one significant way - we have not removed state outlays for CHIP subsidies and supplemental ACA exchange subsidies and added them to Medicaid spending as we did with the federal data. Adjusting “Other health programs” to deduct the impact of federal revenues leaves $154 billion. $154 billion/$3.21 trillion = 4.8%.

TOTAL STATE AND LOCAL: $633.5 billion/$3.2 trillion = 19.74%

Final Summary:

LIMITATIONS

HOW THE ANALYSIS MAY UNDERSTATE HEALTH CARE TAXES AND SPENDING

Contractor Health Insurance: Healing and Stealing assumes three primary types of health care spending: costs of policy-driven health care programs such as Medicare or the expenses of government-owned hospitals that are clearly identified as “health care”; the cost of the government’s provision of health insurance and payment of Medicare payroll taxes for employees regardless of what they work on, and; at the federal level, the tax subsidy for employer-sponsored health insurance.

Our methodology ignores a significant source of government-financed health care spending - the cost of health insurance for workers employed by private firms that contract with the government to perform non-health care work. Beyond the federal agencies identified from FedScope, and our estimate of the percentage of state and local expenditures for health care, we assume that no other expenditures are health care costs. This is unquestionably an inaccurate assumption, one that tends to underestimate the percentage of government spending on health care.

For example, most infrastructure spending on highway construction and mass transit capital projects is spent through private contractors. Industry analysts estimate that labor costs make up between 20% and 40% of the costs of construction projects. In 2022, the federal and state governments spent $232 billion on highway construction, meaning our analysis ignores up to $60 million in federal spending for health insurance and Medicare payroll taxes for construction contractors just for one budgetary line item.

Similarly, beyond the Military Health Services, military and intelligence spending is not counted as health care, but much of it runs through contractors and subcontractors who incur health insurance and Medicare payroll tax costs for their employees. Any spending on non-health care programs that operate through contractors includes health care funded by undocumented taxpayers that is not included in the estimates.

University Medical Practices: Many state universities operate public hospitals, and the Census appears to have captured most, if not all of the hospital spending. However, public medical schools also often operate large faculty-based group physician practices in a variety of different corporate structures. Some of those practices remain distinct from the university’s affiliated hospital and may operate under either the University’s corporate umbrella or a nominally independent but ultimately controlled entity. Depending on how public universities account for physician practice operations, some expenses for these practices may not be reported either in the “hospital” or “health” census categories, although the latter includes the costs of medical education.

Medicaid administrative costs: The cost of health insurance and Medicare payroll taxes for Medicaid workers is likely both overestimated and double-subtracted. First, when deducting the average 5% of Medicaid spent on administration from NHE estimates of government spending on insurance and payroll taxes, we assume all of the administrative costs are for labor, when they’re likely not. Second, the average administrative costs are for federal and state governments combined. The relatively small federal costs for Medicaid administration, including health insurance and Medicare payroll taxes for employees in CMS are already subtracted from federal spending through our analysis of FedScope data, and thus are subtracted twice.

HOW THE ANALYSIS MAY OVERSTATE HEALTH CARE TAXES AND SPENDING

Sales and excise taxes and spending: Some sales and excise taxes are by law supposed to fund specific spending programs. Unlike Social Security and Medicare, however, rather than segregate them as non-health care-related, Healing and Stealing treats these taxes as fungible and analogous to general revenues, for several reasons. To begin with, at the state and local level, ITEP did not provide detailed enough information to separate the various sales and excise taxes from one another, making segregating various taxes and expenditures from the broader pool extremely difficult. Secondly, some taxes ostensibly designated for non-health care purposes are increasingly diverted to other uses. Third, unlike Social Security, which has a very high ratio of spending to staff, spending on labor-intensive programs usually involves hiring contractors, and as noted we have otherwise ignored the “pass-through” effects of contractors’ health insurance and Medicare payroll tax spending.

Most of the “other” federal taxes and a sizable portion of state and local sales and excise taxes estimated by ITEP are fuel taxes and other transportation-related taxes.

However, a majority of states now divert at least some portions of gas taxes to other uses and we don’t have clear estimates of the amount of fuel taxes paid by undocumented taxpayers relative to other sales taxes. Moreover, we’ve already noted the fact that a portion of highway and mass transit construction spending goes to health care for contracted workers, otherwise ignored in the analysis.

Federal fuel taxes fund in part the Highway Trust Fund, which dispenses grants to states for highway and mass transit projects. For the reasons described above, we treat those taxes as if they are available for a portion to be spent on health care. To get a rough sense of the impact of segregating those taxes, we subtracted all $7.62 billion in “miscellaneous” federal taxes paid by undocumented taxpayers from the total, and deducted the entire budget of the Federal Highway Administration and the Federal Mass Transit Administration from the federal denominator. The new estimate would be $20.9 billion in undocumented taxpayers’ spending on health care, still slightly higher than the estimated total cost of undocumented people’s health care, and obviously still a large net subsidy to other U.S. residents given the fact that undocumented residents are mostly ineligible for the health care programs their taxes fund.

II. Total Cost of Health Care For Undocumented Immigrants in the U.S.

[This section has been updated to clarify that the per-person cost of health care calculated by Dr. Wilson et al was for adults]

In a December 3, 2020 JAMA Open Network article, University of Utah economist Fernando Wilson and co-authors estimated that the average amount spent on health care for unauthorized immigrant adults above the age of 18 was $1,629 in 2017:

“Mean annual health care expenditures per person were $1629 (95% CI, $1330-$1928) for unauthorized immigrants, $3795 (95% CI, $3555-$4035) for authorized immigrants, and $6088 (95% CI, $5935-$6242) for US-born individuals.”

To make the numbers comparable to the ITEP tax estimates from 2022, Healing and Stealing obtained from the St. Louis Federal Reserve monthly average seasonally adjusted data for the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: Medical Care, where July 2017 = 476.279 and July 1, 2022 = 549.741, and 549.741 - 476.370 = 73.462 and 73.462/476.370 = .154241527. 1.154241527 * $1,629 = $1,880.26.

These estimates may slightly overstate the cost of health care for undocumented people. Dr. Wilson et al calculated the per-person cost of health care for undocumented adults older than 18. Sub-population estimates of health care costs vary significantly by the characteristics of the larger population. However, children from birth to 18 years typically cost significantly less to take care of than adults. National Health Expenditure data for 2020 shows the following breakdown for total personal health expenditures paid for by all payers by age:

0-18: $4,217

19-44: $6,669

45-64: $12,577

65-84: $20,503

85+: $35,995