Fully Fund Medicare Now!

More Than 1/3 of People on Medicare Skip Health Care Every Year. That's not Okay.

Here’s something you might not expect to read in a newsletter strongly inclined toward Medicare for All: Medicare is crappy. It needs to be fixed now.

Major media are filled with long-overdue stories documenting how private Medicare health insurance plans are ripping off the government and illegally denying claims.

Yes, privatizing Medicare and Medicaid is a terrible idea! Yes, private insurers scam older adults and people with disabilities by promising lower costs if they surrender free choice of providers. Yes, private insurers injure and kill people with tactics like claims denials, making lower cost-sharing meaningless. Yes, the insurance industry drowns politicians in cash to get permission to rob and harm us.

One big reason they get away with it is that the current version of “original” Medicare costs people too much and has serious holes in its benefits. That’s why more than half of people on Medicare are now enrolled in private insurance. They’re lured by lower premiums and gimmicks like gym membership discounts, only to switch back once they get sick and realize they’ve signed away their freedom to see the doctors they need.

When Medicare-for-All campaigners say they’re fighting for “fully-funded, better Medicare for All,” they mean coverage for everyone without the gaps that force people to make choices between bankruptcy and bureaucratic hell. So here is the first of an occasional Healing and Stealing series on Not Very Modest But Nevertheless Incremental Proposals for improving U.S. health care:

Fully Fund Medicare Now. Stop charging people $2,000 a year for their health insurance, stop making them pay deductibles and coinsurance, and add benefits to cover all the health care people need. If you’re in original Medicare this year and have a hospital stay, your total costs will include:

Part B premiums: $1,978.80 Medicare Part B covers doctors, labs, and other non-hospital care. You have to pay an insurance premium to get coverage. Premiums for people in the top 7% of the income scale are higher, but the standard premium is just under $2,000.

Part A deductible: $1,600 Medicare Part A pays for inpatient and outpatient hospital care, but you have to pay $1,600 before your insurance kicks in.

Part B deductible: $237 Separate from the hospital care deductible, you pay $237 for doctors, labs, etc., before Medicare kicks in.

“Coinsurance” after the deductibles: 20%! You pay 20% of Medicare fees after the deductibles for hospital stays, doctor visits, outpatient treatment, etc. There’s no out of pocket cap on these payments.

Part D Premiums and Cost-sharing: Medicare covers prescription drugs through Part D, a fully privatized insurance program. The rules are complex, but enrollees paid $17.9 billion in cost sharing and $22.4 billion in premiums last year.

Leaving aside prescription drugs, that’s $3,804.80 plus 20% of the costs once Medicare starts paying for your care. Not surprisingly, the Commonwealth Fund reported in 2022 that 38% of older adults on Medicare said they skipped a needed test, treatment or prescription because of cost. This might seem easy to fix, but for decades rather than cover all the medical expenses of people older than 65 or with disabilities, Congress just created opportunities for private insurance companies to loot the country:

Medicare Supplemental (“Medigap”) coverage: If you’re in original Medicare, you can buy supplemental insurance to cover some of your out of pocket costs. According to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners’ (NAIC) annual health insurance industry analysis, Medicare supplemental insurance generated $13 billion in premium revenue in 2022, with just 82% of that going to actual medical care.

Medicare Advantage: The big money is in Medicare Advantage (“MA”), the program that allows people on Medicare to get their benefits by enrolling in private health insurance plans. The federal government paid private insurers $405 billion last year, according to Congress’ Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). MedPAC’s March 2023 report lays out why people choose private health plans: “the primary trade-off in choosing between MA and [original Medicare] is access to the additional benefits that plans provide versus an almost unlimited choice of providers available under” original Medicare.

What is now Medicare Advantage was first sold to politicians based on the “efficiency” of private insurance. In 1985, Medicare started paying private insurers 95% of the average spending on Medicare patients for every person who enrolled in a private health plan. Corporate efficiency was supposed to allow insurers to cap out-of-pocket spending, offer relief on cost-sharing and provide a few other extra benefits, with money left over for profit, all while saving 5% off the top for the government.

In real life, people who signed up for MA were much more than 5% healthier than the average person on Medicare. When they got sick, they also tended to return to original Medicare and pile up medical bills, so the public consistently lost big money on private sector efficiency. For 40 years Medicare regulators have tried to figure out new formulas to pay private insurers that don’t waste money.

They failed.

According to MedPAC, “private plans have never been paid less than [original Medicare]” when data are corrected for the health status of people enrolled. Despite constant tinkering with formulas, according to University of Southern California researchers, this year the “favorable selection” that has plagued privatized Medicare for decades, along with bonuses for health plan “quality” that have no factual basis, will lead Medicare to pay private insurers at least $52 billion more than what the program would spend if the relatively healthy people who signed up for MA had stayed in original Medicare.

That’s not all. Federal MA payments are now supposed to be adjusted according to the health risks of people in each plan. The industry has started claiming their patients aren’t as healthy as they really are, an old hospital trick known as “upcoding,” perfected by GOP bandits Rick Scott and the Frist brothers in the 1990s. MedPAC says this “coding intensity” costs Medicare another “6 percent more for MA enrollees than it would spend” in original Medicare. Taken together, Physicians for a National Health Program estimates that these thefts will cost the federal government from $88 to $104 billion this year.

Private insurance inefficiency doesn’t improve access to health care. According to the Commonwealth Fund, patients enrolled in MA plans were more likely to be underinsured (21%-15%) and more likely to report having skipped care due to cost (41%-35%) than patients enrolled in original Medicare (see A Little Extra for the Data Curious below for a caution on these figures).

So U.S. health care policy for the groups of people who most need health care and most likely live on fixed incomes - adults over 65 and people with disabilities - is to make them pay so much money that more than a third of them skip medical, dental and pharmaceutical treatment each year. Moreover, people with disabilities only become eligible for Medicare by qualifying for Social Security Disability Income (SSDI). Yet you have to wait 2 full years before even applying for Medicare, a major burden for people with both chronic and acute health care needs.

This isn’t new - it’s been bipartisan policy for years. To move the country toward real universal health insurance faster than the 500-year timeline the ACA put us on, a logical first step would be to create universal coverage for the people who are supposed to have it already.

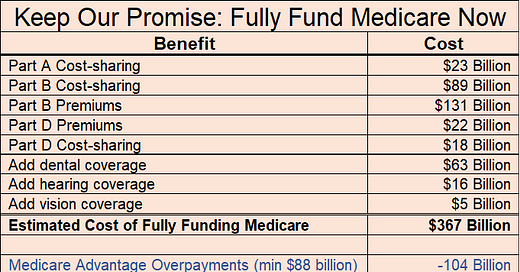

Fully funding Medicare now means eliminating the Part B premiums, the Part A and B deductibles and coinsurance, and prescription drug premiums and cost sharing. It means adding dental, hearing and vision benefits, and making Medicare eligibility automatic when people are approved for SSDI. This will require additional federal spending, but nearly half of the roughly $367 billion that’s needed (see table) is already being spent in Medicare Advantage.

Beyond the up to $104 billion in overpayments identified by PNHP, 17% of payments to private MA health plans - $69 billion - is already supposed to go toward “extra benefits” like reducing Part B premiums and cost-sharing. MedPAC says it has no idea what that money is spent on and what its impact on beneficiaries is. Those dollars could be used immediately to improve original Medicare for everyone.

$173 billion is a good start toward turning Medicare into real coverage for everyone who is eligible. The rest of the money needed can be found in lots of different ways if politicians decide they’re tired of serving corporate power.

Nearly sixty years after Congress and President Johnson promised to protect people with disabilities and adults 65 years and older from illness and injury, it’s time to make good on our word.

A LITTLE EXTRA FOR THE DATA CURIOUS

Favorable Selection Costs “at least $52 billion”: The University of Southern California analysis says that combined favorable selection, quality bonuses and upcoding will result in “at least $75 billion” in overcharges to Medicare. MedPAC, cited in the USC analysis, says that upcoding and quality bonuses will cost 6% of total payments to Medicare Advantage plans, or $23 billion. So: 75 - 23 = 52.

MA Enrollees More Likely to be Underinsured and Skip Care: Commonwealth asked people if they had skipped different types of care in the past year. They divided up the responses by what type of insurance people had at the time of the survey. A lot of people switch back and forth between original Medicare and Medicare Advantage, so a significant number of people may have skipped care when they were in original Medicare, but were enrolled in MA by the time they talked to Commonwealth.

It’s impossible to pinpoint the potential impact of this phenomenon on the survey results. At its most extreme it might reduce the percentage of people who skipped care while enrolled in an MA plan to a little less than a third, still a startling result for a program whose primary value to people is that it reduces their cost sharing.

Between 2017 and 2022, an average of 13% of people in Medicare Advantage voluntarily quit their plans, with some enrolling in another plan and others returning to original Medicare. 2022 was the highest disenrollment year, at 17%. At the same time, the overall percentage of people eligible for Medicare enrolled in an MA plan grew by 3% per year, which means that the people leaving would have to be replaced, plus an additional 3% of the entire Medicare population. Slightly less than half of the eligible Medicare population was enrolled in MA in 2022. So if we assume that every person who disenrolled was replaced by someone coming into MA from original Medicare, that would be roughly 8% of the sample. Add another 3% on top, and the maximum possible impact would be ~11% if we assume that every single one of those people skipped care in original Medicare. It’s safe to say that more than a third of MA enrollees skipped care.

PNHP $88-$104 Billion: Readers who follow the PNHP link will see reporting on another $36 billion in possible overpayment due to “induced utilization” in pricing benchmarks. This is a highly technical issue, but Healing and Stealing believes that “Induced Utilization” as a concept validates the false belief that we get too much health care and that more insurance means more unnecessary care. The high end number of $140 billion in the otherwise excellent PNHP report is, from this perspective, overstated. $88-$104 billion in overpayments when combined with the $69 billion in opaque MA spending on extra benefits that is excluded from PNHP’s analysis adds up to a big head start toward fully funding Medicare.

Part A Cost-Sharing: MedPAC March 2023, page 20.: average part A cost-sharing in original Medicare was $383. We multiplied that times the total number of people in Part A and B, regardless whether they were in MA.

Part B Premiums: According to the Congressional Budget Office, combined Part B premiums and inflation rebates to the federal government for drugs paid under part B were $130 billion in 2022 and projected to be $137 billion in 2023. We haven’t found a source that disaggregates the two, so we’re taking PNHP’s word for $131 billion.

Part B Cost-sharing: MedPAC March 2023, page 20. As with Part A, the chart assumes the average of $1,469 applies to all beneficiaries, ultimately partially offset by “extra benefits” spending. Given that MA patients are much healthier, likely to use significantly less health care and therefor incur lower out of pocket costs, the assumptions about the cost of Medicare paying current Part A and Part B cost-sharing are conservative (i.e. overestimates of the costs).

Part D Premiums and Cost-sharing: MedPAC March 2023, page 383, The analysis includes only those costs currently borne by individuals on the assumption that current levels of spending by Medicare are given. “Beyond program spending, Part D plan enrollees paid $17.9 billion in cost sharing and $7.5 billion in premiums for enhanced benefits.”

Medicare Advantage Extra Benefit Spending: Explained in the text. We calculated how much it would cost to close all gaps assuming that everyone had original Medicare, and subtract the portion of MA premiums that supposedly go to “extra benefits.” As with much of the program, there is little accountability. According to MedPAC “we do not have reliable information about the extent to which beneficiaries use or value these benefits nor information about their value to beneficiaries.”

Dental, Hearing and Vision Benefits: CBO analysis from 2019. h/t PNHP.