We Don't Get Too Much Health Care

Most of What You Need to Know About U.S. Health Care in 4 Pictures

First, apologies. My computer collapsed and I lost a huge amount of data, including two article drafts. Technology catastrophes are never well-timed, but right after launching Healing and Stealing with a promise of a weekly publication was a special nightmare.

Health care experts, politicians and journalists will often say - or imply - that patients who want or get too much health care, and doctors who deliver too much to them are significantly responsible for high U.S. health care costs. There’s powerful evidence contradicting this belief, but that doesn’t seem to have much effect on our health care “thought leaders.”

Deeply held beliefs about how health care works can influence the way policymakers address or - or don’t - the ongoing medical and financial disaster of American health care. What follows is nearly everything you need to know about U.S. health care spending in four simple visuals.

First, two examples of “Americans want and get too much health care” thinking:

The Affordable Care Act included a tax on job-based health insurance plans that the Obama Administration thought were too generous. The “Cadillac Tax” was supposed to control the the cost of health insurance by raising premiums, or in the White House’s memorable phrase, giving workers more “skin in the game.”

Academics have spent years warning of the danger of paying for health care as piece work, known as “fee-for-service.” As the Commonwealth Fund put it in February, “Under fee-for-service, health care providers like physicians and hospitals are paid for each service they provide. In other words, they are rewarded for volume — they are paid more if they deliver more services, even if they don’t achieve desired results.“

It’s a seductive, puritanical American story. Patients luxuriating in “Cadillac” insurance. Greedy doctors ordering millions of unnecessary tests and procedures to buy their beach houses.

It’s also false. Not true. Refuted by the largest body of evidence imaginable.

In the dark corners of U.S. health care, unscrupulous practitioners do oversell products and services. Congress and regulators have struggled since 1989 to prevent doctors from profiting by referring patients to facilities in which they or their families have a financial interest. Insurance plans often have a bias for prescription drugs over visits to human medical professionals. And one of the symptoms of “illness anxiety disorder” can be “frequently making medical appointments for reassurance.”

But as a society we do not get too much health care. We get too little. To the extent that we do get too much of the wrong kind of health care, that’s not what makes us spend staggering sums of money.

This shouldn’t be a controversial idea. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development collects the results of billions of encounters between patients, doctors and hospitals all over the planet. When you compare the U.S. with the 15 other major countries that spend the most money per person on health care and whose populations and economies look the most like the U.S., it gets tough to sustain the notion that we spend so much money because we want and get too much health care. To summarize:

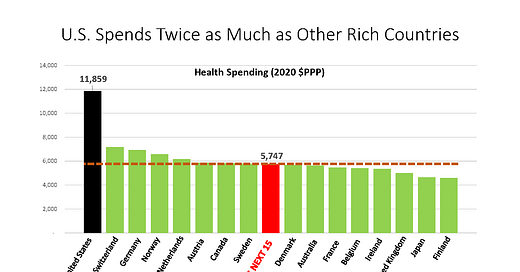

We spend twice as much as other countries on average.

We go to the hospital and see our doctors less often than people in those countries.

When Americans do get health care, we spend much more out of pocket than everyone else except people in Switzerland.

We Spend Twice as Much Money: The U.S. spends twice as much money per person on health care than the average of other rich countries. This isn’t comparing the U.S. to the whole world, but to the next 15 most expensive health care systems on the planet. Not only does the U.S. spend the most, we’re runaway winners, spending 65% more than the silver medalist, Switzerland.

[Sources: 2020 data. Link to the OECD database for all four graphs here. For 1st graph, select “Health expenditure and financing”, then on the “Measure” menu, select “Per capita, current prices, current PPPs.”]

We Go to the Hospital Less Often: Hospital care is the biggest single part of health spending across the world. Although the U.S. spends wildly more on “health care,” people in other countries are treated as inpatients in hospitals more than 50% more often than Americans. Whatever we’re paying for, we’re not taking vacations in the ICU.

[2019 Data. At OECD select “Health Care Utilisation” > “Hospital aggregates” >> variable = “hospital disccharges - all hospitals.” U.S. data from the American Hospital Association via CDC here. Read appendix “A Little Extra for the Data Curious” to learn how petty corruption requires two sources.]

We See the Doctor Less Often: Hospitals are expensive and can be dangerous, right? So private insurers and governments are doing a good job and we’re getting health care where we should - in our doctors’ offices and clinics instead of a hospital bed, right?

Nope. We also go to the doctor less often than people in other countries that spend a lot less money that we do.

[2019 data except Switzerland (2017) and U.S. (2011). At OECD select “Health Care Utilisation” > “consultations.” Appendix “A Little Extra for the Data Curious” describes the old U.S. data]

We Spend More Out of Pocket than Everyone Except People in Switzerland: When we finally do get health care, we spend 50% more “out of pocket” than people in other rich countries, meaning payments for doctors, hospitals and drugs beyond the cost of buying health insurance.

[2019 data. At OECD select “Health expenditure and financing” > financing scheme = “Household out-of-pocket payments.”]

If the U.S. spends so much as a society in part because we want and doctors give us too much health care, there should be a potent logic to policies that hold down national costs by forcing patients to pay more out of pocket to discourage them from going to the doctor or the hospital.

There isn’t. The U.S. has already tried and failed to control overall costs by making people pay more money directly to hospitals, doctors and pharmacies on a nearly unimaginable scale. It hasn’t worked, doesn’t work and won’t work.

Yet at every turn, American patients are bludgeoned by people with power who act as if lust for unnecessary medical treatment is a core problem. Insurance companies enforce this belief at several steps in patients’ care, starting with “prior authorization” for major treatments and ending with refusals to pay. An entire consulting industry has grown up to help with this work. KFF Health News reports that artificial intelligence algorithms are starting to make these decisions, including a company that sent a denial letter to an infant.

One of several things we’ll be doing at Healing and Stealing is examining the (very large) flow of money that keeps ideas like “we want too much health care and docs give us too much” embedded in our media and politics even when evidence from billions of patient encounters flatly contradicts them. Stay tuned.

It would be irresponsible not to address the obvious - if overtreatment isn’t the cause of massive health care spending, what is? For my money, there are three drivers.

Unregulated profit-generating monopoly pricing. Most policy discussions focus more on the “monopoly” rather than the “unregulated” issue, but at least this is no longer taboo in polite circles.

Insane administrative costs. The true genius of American health care is finding new ways to steal our time and crush our souls with ever more meaningless paperwork, emails to human resources, phone calls with government administrators, private insurers and hospital debt collectors, time missed from work to deal with bureaucratic nightmares, extra time working to pay for health care and delayed or missed health care.

Epic elite ideological stupidity. The third driver is a simple idea that binds the first two together. More soon.

A LITTLE EXTRA FOR THE DATA CURIOUS

Healing and Stealing believes in full data transparency, so here’s an explanation of the numbers in the graphs. The OECD database can be challenging, so if you try to retrace the research steps and have trouble, drop a note in the comments. This post is way past due, so I’ll try to add the tables at the bottom of the post once I clean them up, especially the hospital table, which includes non-OECD sourcing.

The text compares the U.S. with 15 other countries, with a couple of caveats. Luxembourg would be among the top 15 based on per capita spending, but was excluded because it is so tiny. Not every country reports for every metric. The Netherlands and Germany are absent from the hospital graph and the UK from the doctor consultation data.

The averages for the two spending metrics do not include the U.S. because the level of spending tends to distort the average. The averages for the two utilization measures do include the U.S.

We Spend Twice as Much: The two most credible ways to measure national health spending for international comparisons are as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP%) and “purchasing power parities” dollars (PPP). Both are calculated per person in the country, or “per capita.”

GDP is one of several ways to measure the size of a country’s economy. Health care as a percentage of GDP shows what part of a country’s overall economy is consumed by health spending. The advantage of GDP% is that it measures the social burden of health spending relative to a society’s other needs. If Country A’s total GDP per capita is twice Country B’s, each health dollar spent will be twice the burden on people in Country B than it will be in Country A.

PPP shows how much money was actually spent per person in each country, measured in dollars. “Purchasing Price Parities” is a technique to adjust the dollar spending to account for the structure of each country’s economy - differences in supply chains or inflation, for example - to yield a credible measure of actual spending across economies.

Neither measure is perfect. Healing and Stealing uses PPP dollars because percent of GDP is a software cheat that makes the U.S. look better than it is.

U.S. health spending in 2020 was 18.8% of GDP, the average among the top 16 systems was 11.6% and the second highest spender, Canada, spent 12.9% of GDP on health care.

Of course, “wait, we only spend 60% more than everyone else, not double” isn’t a much of a critique. The critical point is that the U.S. health care system is so wildly bloated that it artificially inflates the size of GDP. Using GDP% means measuring the bloated, deadly U.S. health care industry against a GDP that is artificially large because of the bloated, deadly U.S. health care industry, effectively legitimizing a crime against humanity. Count Healing and Stealing out.

We Go to the Hospital Less Often: Data are from 2019 to maximize the number of countries reporting and minimize the impact of dramatic changes in utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic on the comparison. This graph draws from two sources due to a bit of cheesy U.S. health care corruption.

OECD asks member nations to report a top line number for discharges from all hospitals. Their tables on hospital stays don’t include the U.S. When Healing and Stealing asked OECD staff why they didn’t have the U.S. numbers, they said that their rules require data sets to be available for free to member countries.

Turns out the only people with that information in the U.S. is the American Hospital Association, which conducts an annual survey that is nearly a complete census of American hospitals. This being the United States of America, the AHA makes money by putting most of the survey data behind a paywall and collecting thousands of dollars from hospitals, insurance companies, media outlets, academics, doctor practices and anyone else interested in how the hospital industry heals us and fleeces us.

AHA does publish a public “you-can-only-read-this-on-the-web” version of some of the indicators from the survey, which includes a number for hospital admissions. CDC republished those numbers as a measure of all hospital stays in the U.S. So that’s what we’ve got. There may be a small statistical difference in the definition of an “admission” by the AHA and the way some OECD member countries count “discharges,” but not enough to change the fact that people in the U.S. go to the hospital a lot less often than the average for other rich countries.

Also worth noting, when I asked AHA if their “admissions” numbers were equivalent to the discharge data from other OECD countries, they wouldn’t give an answer, and referred Healing and Stealing to the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project at the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP publishes state-level discharge data for almost all states. Unfortunately, those data don’t include federally-owned hospitals and a small class of long-term hospitals, so even if Healing and Stealing took the time to add the state numbers together, they would be off. AHRQ is a marvelous agency and brings real talent and rigor to their work. But neither they, nor CDC nor anyone else in the U.S. government can muster what should be the simplest possible metric at a national level and report it to an international body, while policymakers allow the hospital industry to hoard the core data behind a very American paywall.

Of course, the U.S. public has already paid for all of the data a thousand times over. Our insurance premiums, out of pocket payments to hospitals, federal and state taxes to support government insurance programs, radically higher property and business taxes to offset the tax breaks given to the 60% of the AHA member hospitals that are private “charities” all fund the hardware, software and staff necessary to gather and analyze this information. And, of course, AHA is itself a tax exempt organization.

We Go to the Doctor Less Often: This metric has the highest probability of inaccuracy of the four, but in the end, it’s pretty good. As with hospitals, the U.S. hasn’t bothered reporting physician consultation data to OECD since 2011. At some point, Healing and Stealing will assemble the equivalent metric and readers will be the first to have it, but it’s a complex data gathering and analysis project for another day.

So for now we do what other researchers do - squint and compare “the most recent data for each country,” which means comparing 11 year old U.S. data to much more recent information from other countries. As with hospitalization, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in sudden changes in the rates of doctor consultations, and France hasn’t yet reported 2020 numbers, so the graph compares the more “normal” 2019 data for all reporting countries except Switzerland (2017) to the aging U.S. data.

Doctor visits tend to be fairly stable over time. Given that more than a third of American adults have been telling the Commonwealth Fund that they skipped or delayed needed medical treatment due to cost in the past year for two decades (see “The Health Care Long March”); that the U.S. has fewer physicians per 1,000 population than all of the 15 countries we’ve looked at except Japan [OECD select “Health Care Resources” > “physicians” » variable = “practising physicians” »> measure = “density per 1,000 population (head counts)”]; that the growth rate of the U.S. physician workforce is slower than all but three other countries, and; the inordinate amount of time U.S. doctors spend on administration, there’s no reason to think that the older U.S. data is inconsistent with people in other countries consulting doctors more often than Americans.

We Spend More Out of Pocket than Anyone Except People in Switzerland: As with overall spending, this is drawn from OECD comparison tables, measured in PPP dollars.