On March 4, a group of hospitals and doctors’ practices decided not to accept a settlement in a series of class-action lawsuits against the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, and filed new lawsuits. The cases raise an important policy question: can anti-trust litigation offer a meaningful remedy to runaway health care prices and flimsy insurance plans that leave millions of people facing bankruptcy? Healing and Stealing has formulated a measured, thoughtful, deeply researched, data-driven answer:

Have you taken leave of your senses? When loan sharks battle protection racketeers, do crime victims win?

In 2012, employers and providers started suing the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association (BCBSA) and more than 30 regional companies operating under the “Blue” brands in all 50 states, Washington, DC and Puerto Rico. Employers claimed that BCBSA policies illegally prohibit state and regional Blue Cross/Blue Shield plans, who are supposed to be independent companies licensing the Blue brands, from competing with each other to sell insurance and administrative services to employers.

Hospitals, doctors and other providers similarly alleged that BCBSA-licensed companies colluded not to compete with each other so no state’s Blue-branded insurer would be undercut by another Blue licensee offering providers higher rates to entice them to participate in networks. Lawyers representing some providers reached a settlement last fall with BCBSA and its regional affiliates, approved by U.S. District Court Judge R. David Proctor on December 4, 2024.

As usual, BCBSA and its affiliates admitted no wrongdoing in the provider cases. They agreed to pay $2.8 billion in damages for 16 years worth of harm to the hospitals and doctors who sued them; change their policies to allow licensed affiliates to compete with one another on the terms of network participation; speed up reimbursements, and; make rules for reimbursement and claims denials clearer. The settlement will be overseen by a joint Monitoring Committee for the next five years.

Although the settlement potentially affects every provider in the U.S., Judge Proctor’s order doesn’t force hospitals, physicians and other providers to accept the terms. He set March 4 as a deadline for providers to decide whether to “opt-out” and sue on their own for a better recovery. More than 60 hospital systems and physician practices filed six different lawsuits in federal courts in Illinois, Pennsylvania and California restating the allegations against BCBSA and its affiliates (Complaints here, here, here, here, here and here).

The 12 year litigation, settlement and the new opt-out cases open a window into the operations of health care businesses and the catastrophic failure of markets to organize health care for benefit of the the public at large.

The settlement amount is laughably small for the expenses and effort of the litigation - a fraction of a rounding error in the U.S.’s $4.9 trillion health care economy. Moreover, the plaintiffs who were supposedly harmed include some of the most aggressive monopolists since Teddy Roosevelt started busting trusts - hospital systems who wield pricing power in highly concentrated local and regional health care markets.

Mountains of Paper and Expert Seminars: Judge Proctor described what sounds on first reading like an epic legal war. Over 12 years, the Blue Cross defendants produced 75 million pages of documents and the plaintiffs another 1.5 million of their own, after 30 discovery hearings and 91 discovery orders, requiring 164,000 hours of manual review by court officials. The settlement was reached through nine years of mediation by three mediators, including “dozens of in-person mediation sessions and countless calls and virtual meetings.”

The case even gave everyone the chance to go to health care economics school:

In 2016 and 2017, the parties participated in two “Economics Day” sessions with the court. During these sessions the parties prepared and presented tutorials, including expert testimony and other evidence, to educate the court about the economic theories of the case and the business structures of the Blues challenged in this litigation.

A Microscopic Speck on a Rounding Error: After all that, the Blues agreed to a payment that won’t even register on U.S. health care spending. Attorneys fees and other expenses will knock the $2.8 billion down to roughly an even $2 billion, or four tenths of 1 percent of 2023’s $4.9 trillion National Health Expenditures.

The payment is supposed to make providers whole for sixteen years of alleged wrongdoing. There’s a fancy calculation to make the outlines of this speck on a rounding error precise, but crudely, 1/16 of $2 billion is $125 million, or a whopping 0.003% of 2023 National Health Expenditures.

Hospitals and “other facilities” are supposed to split 92% of the payout. Each individual hospital’s slice depends on the volume of claims affected by the alleged misconduct submitted to the various Blue Cross plans over the years. Many other providers are entitled to a cut, but if we assume (before the opt outs) that all of the “facilities” portion only goes to the nation’s 5,112 non-federal community hospitals, each hospital would receive an average of $359,937, or a grand total of $22,496 per hospital per year.

Pot, Meet Kettle: Beyond the pittance delivered by 12 years of high stakes litigation, the cases expose two ways in which distributing health care through private transactions simply hasn’t worked and won’t work.

First, this is another example of the private insurance industry’s inability or refusal to do the job we’ve given it. According to one of the new lawsuits filed by Roman Catholic Church-affiliated hospital corporation CommonSpirit, the Blues began a “Market Allocation Conspiracy” and related “Price Fixing Conspiracy” that forced CommonSpirit “to accept the below-market reimbursements set by Defendants” for the past 16 years.

According the complaint in another of the new cases led by Catholic giant Bon Secours Mercy Health, Blue Cross originated in Minnesota in 1937 and Blue Shield two years later in western New York. Blue Cross offered insurance for hospital care, Blue Shield for physician services. The American Hospital Association registered the Blue Cross trademark in the late 1940s and formed a commission to approve Blue Cross licenses. As the number of Blue Shield plans grew, they created their own standard-setting organization.

The AHA relinquished control of the Blue Cross brand to an association controlled by the plans themselves in 1972. Local insurers under each brand soon began offering both hospital and physician coverage to meet employer customers’ expectations for comprehensive coverage. The Blue Cross and Blue Shield national organizations merged in 1982 to form BCBSA.

Paying hospitals and doctors is the main cost for health insurers. Having a bunch of plans called “Blue Cross/Blue Shield” negotiating separate rates would indeed allow the hospitals to negotiate increasingly high prices. So the Blues limited licenses to one per state and prohibited different Blues from negotiating rates in competition with each other. Yet they still claimed that each separate licensed plan is an independent corporation. That contradiction is the basis for the alleged Market Allocation Conspiracy and related Price Fixing Conspiracy.

Yet, even with these illegal, Scarily Capitalized Conspiracies at their disposal, whatever money the Blue Cross insurers saved with their below-market payments to hospitals somehow failed to make a dent in the growth of insurance premiums between 2008 and 2024. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, employer-sponsored premiums for family coverage grew by 102% over the period covered by the lawsuits, more than twice the rate of consumer prices generally.

Of course, the Blues were allegedly simultaneously conspiring not to compete with each other to offer lower premiums to employers and individuals. Those cases settled for a similar $2.7 billion and similar promises by the association not to prohibit Blues from competing with each other to sell insurance plans.

The Blues’ behavior toward both plaintiffs’ groups, if true as alleged, does make private insurers seem like gangsters. At the same time, if, as the plaintiffs themselves complain, more competition means higher hospital prices, it’s difficult to imagine how competition will ultimately lower premiums, no matter how fervently one believes in market magic.

In the real world, many of the alleged victims in the provider cases exercise their own monopoly pricing power in negotiations with health insurers, and behave with impunity in other aspects of their relationships with their patients and communities.

Hospital Market Power: The American Medical Association sponsors research into the market power of both insurers and hospitals, using the Census Bureau’s Metropolitan Statistical Areas to define “market” boundaries and the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), a standard academic measure, to estimate how concentrated each market is. HHI is measured on a scale of 1 to 10,000, with 10,000 a perfect monopoly.

As of 2021, 99% of all hospital markets made up of less than 3 million people in the U.S. had an HHI greater than 1,8000 for the hospital industry, which meets the Department of Justice’s definition of a “highly concentrated” market that offers little hospital competition.

So, pretty much all of them.

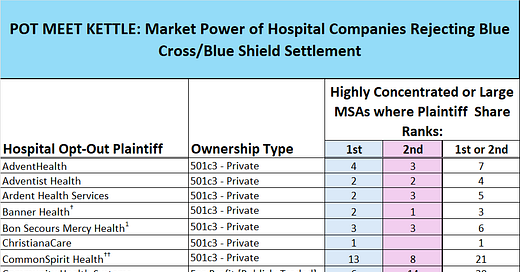

Healing and Stealing examined the filings in the six new anti-trust suits and identified at least 62 topline provider companies, 58 of which are hospitals or multi-hospital health systems. Checking the lawsuits against the AMA’s market analysis, at least 47 of the hospital plaintiffs have either the largest or second-largest market share of hospital care in one or more highly consolidated MSAs as measured by HHI or in one of the 13 MSAs that are bigger than 3 million people.

Two caveats: the AMA didn’t calculate HHI for 13 MSAs with more than 3 million people, because they aren’t single “markets” and defining real submarkets is a headache. But they often aren’t competitive either, so we included them. We also probably missed some MSAs where plaintiffs have monopoly power. We caught a few changes, but hospital corporations are constantly merging and changing their names, so a few companies identified by the AMA in 2021 that were bought out or rebranded themselves may have escaped notice. More at A Little Extra for the Data Curious below.

The opt-out plaintiffs aren’t unique in holding pricing power. For-profit HCA, which has the largest or 2nd biggest market share in 38 highly consolidated MSAs, accepted the settlement. However, by refiling their anti-trust cases the opting out hospitals deserve additional scrutiny for their own behavior. And there’s no better place to start than CommonSpirit, the nation’s largest private tax exempt hospital corporation.

A Spiritual Giant: CommonSpirit is organized as a 501c(3) not-for-profit “charitable” corporation. The company grew through a dizzying array of mergers among Roman Catholic religious orders and now has 157 hospitals and 2,300 “care sites” in 24 states, according to a company presentation at the annual JP Morgan health care conference. They deliver “20 million patient encounters annually.” Sixteen years of brutalization at the hands of The Blues didn’t prevent CommonSpirit from paying former CEO Lloyd Dean a total of $64 million in total compensation in 2022 and 2023 for 13 months of work and a gentle golden parachute ride.

According to the AMA study, in 2021 CommonSpirit was one of the two largest hospital operators in 20 separate heavily concentrated hospital services markets. And although the researchers gave up trying to slice the Phoenix-Mesa-Chandler, Arizona region into submarkets so they could calculate a formal measure of consolidation, CommonSpirit is the second largest hospital company in the whole 4.9 million-resident metropolitan area, accounting for 17% of all inpatient business (fellow opt-out plaintiff tax-exempt Banner Health accounted for 47% of all hospital care in the region).

CommonSpirit’s Hospital of the Future: Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield of Colorado is an alleged member of the 16-year Price Fixing Conspiracy. Yet despite being swindled for a decade and a half by Anthem in Colorado, CommmonSpirit still managed to scrape together $180 million to build a new 72-bed specialty hospital in Colorado Springs, described by CommonSpirit’s local CEO Patrick Sharp as “the hospital of the future,” to help the company “amplify wholeness and healing” in the area.

St. Francis Interquest hospital opened in July 2023, with 10 operating rooms “specifically designed for orthopedic and spine surgery and equipped for robotic procedures,” according to local website Springsmag. It includes the first full-service hospital-based emergency department on Colorado Springs’ “rapidly growing north side.”

The Colorado Springs MSA is split evenly between two hospital operators, Commonspirit and the University of Colorado’s UCHealth system (for data nerds, HHI = 5004). UCHealth had 51% market share in 2021, CommonSpirit 49%. Its new hospital may have tipped CommonSpirit over the top as number one since the AMA analysis. Or UC’s own new north Colorado Springs medical center may have helped them hold onto the top spot by a few percentage points, but it doesn’t really matter. It’s nearly impossible to run an insurance plan in such a heavily concentrated market by cutting one system out,† which means the hospitals had and have real pricing leverage.

Hostage Taking in Colorado (And Elsewhere): What does “pricing leverage” mean for hospitals? The Colorado franchisee of the Blue Price Fixing Conspiracy gave its version to Anthem plan members last year. The contract that sets rates for CommonSpirit’s in-network status as a preferred provider in Anthem’s Colorado networks was set to expire May 1, 2024. The negotiations erupted into a ritual medieval morality play that nearly every state has witnessed in recent years.

Failing to reach agreement would mean thousands of patients would have to pay out of network copays and coinsurance at CommonSpirit’s hospitals. As Healing and Stealing readers know, hospital systems now employ the majority of physicians, so many patients also faced the possibility of needing to switch doctors to afford care.

The parties’ communications teams worked overtime pointing fingers at each other while wrapping themselves in the mantle of concern for patients’ and employers’ physical, mental and financial health. According to CBS KKTV-11 News in Colorado Springs, CommonSpirit claimed that Anthem was offering rate increases below the rate of inflation. “Our ongoing, good-faith negotiations aim to safeguard patient care and protect their choice of doctors by keeping our healthcare services in-network for Anthem members,” the company said in a statement.

In response, Anthem said “CommonSpirit has informed us that if we do not agree to reimbursement rate increases more than twice the rate of inflation, they will leave our health plan networks starting May 1, 2024.” The alleged Price Fixing Conspirators told KKTV that allegedly Aggrieved Anti-Trust Plaintiff CommonSpirit’s services are rather expensive:

“Emergency room rates at CommonSpirit mountain and rural facilities are 232 % higher than all other nearby health systems.”

“Emergency room rates at CommonSpirit Front Range facilities are 45 % higher than all other nearby health systems.” [“Front Range” = the easternmost range of the Rockies in central Colorado, where Denver is located -ed.]

“CommonSpirit’s St Anthony Summit Hospital in Frisco is the most expensive hospital in the state.”

The dispute carried past the May 1 contract expiration, throwing patients’, doctors’ and other providers’ lives into chaos. Then, as almost always happens in these disputes, they settled two weeks later Despite months of stoking public fear and anger focused on the possibility of unreasonably high or dangerously low rate increases, the Denver Post reported that neither side “released any information about the rates they ultimately agreed on.”

Public network contract price fights are now a regular feature of the U.S. health care landscape - CommonSpirit and the Tennessee Alleged Blue Price Fixer performed the same ritual a few weeks later in Chattanooga. The combatants hold communities hostage attempting to extract money from each other, before suddenly ceasing communications after settling. Sometimes hospitals win. Sometimes insurers win. Patients rarely do. However, this pattern is a reminder that multi-billion dollar hospital corporations including nominal “charities” like CommonSpirit are anything but helpless victims of economic warfare.

Other Old Friends: Perhaps the opting out providers are right - the settlement just wasn’t good enough to compensate them for the Blues’ alleged wrongdoing. But we should bear in mind that any new settlement payments ultimately come out of our taxes and premiums. A study by the International Federation of Health Plans and the Health Care Cost Institute of 2022 prices for 12 inpatient procedures across 5 different countries found that US prices were the highest for all 10 by at least 20 percentage points, and on only two of them did the silver medalist exceed 70% of the U.S. price.

Many of the opt-out plaintifs have grabbed headlines for various reasons over the years, but here are two more, one familiar already to Healing and Stealing readers. The other has a very big day today!

Jefferson Health: Sixteen years of alleged illegal collusion by Blue Cross plans didn’t stop Philadelphia’s Thomas Jefferson University hospital system from growing into the largest employer in the state of Pennsylvania after its market power helped hasten the demise of nearby Hahnemann Hospital. In 2021, Jefferson held the largest market position in the 2 million person Philadelphia MSA (32%). Jefferson’s merger with the Lehigh Valley Health System created a $14 billion, 30 hospital system across Eastern Pennsylvania, and added the Allentown (51%) and East Stroudsburg (54%) metro areas to the highly concentrated markets where they are the largest system.

Bon Secours Mercy Health: The New York Times’ 2022 “Profits over Patients” series made the $13.3 billion 50-hospital Catholic chain’s operations in Richmond VA an example of non-profits using unmerciful debt collection tactics against impoverished patients while extracting profits from safety net hospitals. Bon Secours Mercy is the largest provider in 3 highly consolidated markets and second in three others.† Four of those six markets are in Ohio or straddle its borders, where, along with Virginia, the system’s network contract with some CIGNA plans expired today (4/1/25) amidst the usual panicked media coverage as the deadline looms.

If you happen to be a CIGNA subscriber in Ohio or Richmond today who has a doctor employed by Bon Secours, Healing and Stealing sincerely hopes that the anxiety of being torn apart by corporate giants doesn’t harm your physical or mental health. Try to remain calm while scouring your provider directory for a new doctor. These disputes usually settle after scaring the hell out of us, so with a little luck you’ll probably end up being able to see your current doctors and go to your local hospital.

If CIGNA and Bon Secours don’t settle and your health care world is turned fully upside down, you may get very angry. Rightly so. But don’t waste too much energy on the ineffectual thieves at CIGNA who somehow can’t keep your premiums and deductibles from going up every year or the phony charity that dominates the health care delivery system in your town. They’re fighting over spoils they’ve already looted from us under laws that allow them to do it. This is the system that Congress and Presidents of both parties wanted and have designed over 50 years.

Our politicians have convinced themselves that negotiated networks will control costs and deliver high quality health care, although the legal framework might need an occasional tweak. Even if they don’t actually believe it, they pretend they do because actually threatening the insurance or hospital industry instead of posturing at hearings isn’t a great path to re-election, at least not yet. The next time you read news about an impending network contract train wreck, remember that it’s supposed to go down this way. Networks, and therefor network rate negotiations are the core bipartisan cost control and access strategy of U.S. health care.

Faith in competitive markets as a remedy for our health care ills and the need for regulation and litigation to ensure the efficient operation of health care markets is a bipartisan article of faith. Last week the Trump Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division launched an Anticompetitive Regulations Task Force to find and get rid of federal and state regulations that hinder competition. Save for framing “regulations” instead of the actual market behavior as the key problem, the language is nearly indistinguishable from the Biden Administration’s antitrust enforcers.

There is no more reason to believe the Republican approach to encouraging competition will do any more to control costs or improve access than either the current Democratic antitrust fever or a dozen years of courtroom antitrust warfare between two gangs that neither party really wants to challenge. For all their size and profits, private health insurance corporations have neither the power nor the desire to control the price of hospital services. The sooner our political leaders abandon that fantasy and insist on uniform, transparent prices paid by a consolidated public insurer, the sooner we’ll stop skipping health care because we can’t afford it.

†The original article incorrectly stated that Bon Secours Mercy has the highest market share in 4 MSAs and is second in 2. The correct numbers are 3 and 3. Healing and Stealing regrets the error.

A LITTLE EXTRA FOR THE DATA (AND HISTORY) CURIOUS

*Hospital Plaintiffs: Healing and Stealing copied the names of the plaintiffs from documents in the six cases. In each case, lawyers distinguished between parent organizations and affiliates or subsidiaries, but not always in the same format. It’s possible that Healing and Stealing mistook some subsidiary plaintiffs as corporate parents or missed corporate parents on the assumption that they were subsidiaries. The AMA researchers did not necessarily use the same names as the plaintiffs’ attorneys, so each plaintiff was checked against company websites, news accounts and other sources. Please let us know if you spot any inaccuracies and we’ll correct them.

-Settlement Size: Judge Proctor’s order outlines the allocation of the settlment as well as the likely fees and expenses. NHE Table 1 shows $4.9 trillion in total national health expenditures. The American Hospital Association maintains the most accurate census of hospitals. Latest topline numbers are here. The rest is basic arithmetic.

-HHI, MSAs and the AMA data: The AMA data should be taken as a general illustration of the problem of hospital market concentration, and not a specific guide to problems in particular regions. A spreadsheet that shows the results by MSA and system is attached. The information in this article is an analysis by Healing and Stealing of original data published by the American Medical Association. Except where the AMA’s underlying data might be incorrect, any and all errors of fact or analysis are solely Healing and Stealing’s responsibility. The AMA had no role whatsoever in the article - we did not contact them.

HHI is measured on a scale of 1 to 10,000 with a simple formula - measure the market share of each business, square it and add them together (i.e. in a perfect monopoly 100 * 100 = 10,000). HHI used across all industries, but isn’t a perfect measure for hospital care because communities are not going to build an unlimited number of hospitals. Nor are MSAs real market boundaries. MSAs are centered around population clusters of 50,000 people or more. Lawyers and economists have been arguing in court for decades about how “substitutable” hospital care is both within and across MSA boundaries. Can or will patients travel 20 miles? 30 miles? And “hospitals” aren’t generic - even if you draw a reasonable boundary around what looks like a “market” for general hospital services that looks competitive, some hospitals may dominate particular subspecialty services and become impossible for insurers to cut out.