More Insurers Face "Medical Loss" Crises

Paying for the Care Your Customers Paid You for Really Is Bad Business

Healing and Stealing is working on a multi-part analysis of the Medicaid politics surrounding the Republicans’ Big, Ugly budget reconciliation bill (spoiler: the two parties agree on a lot more than the headlines suggest). At the same time, patients enrolled by three more private insurance companies are trying to get the health care they paid for, and Wall Street is nervous and angry.

In the past three weeks, Centene Corporation and Molina Healthcare Inc. have warned investors that patients in some of their plans are sicker than the companies thought or otherwise want too much medical care. As a result, they expect somewhat lower profits for 2025. Earlier in the year, Elevance Health Inc., the insurer formerly known as Anthem, also said its plans have sicker patients this year. These actions follow CVS/Aetna’s announced withdrawal from ACA exchange markets, and UnitedHealth Group’s cancellation of its profit predictions for 2025, as we reported last month.

The news that patients with many different types of health insurance are trying to get health care is driving insurance companies’ stock prices down, although so far none of the insurers predict they will actually lose money. They just think they’ll make less profit than they believed they would at the beginning of the year.

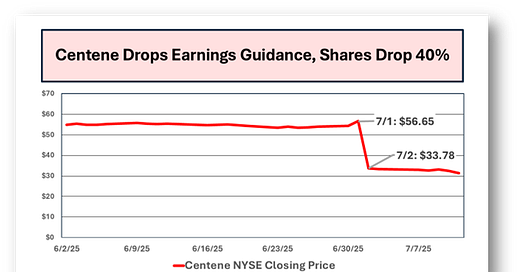

Centene Corporation: Centene touched off the latest panic on July 1, when it abandoned its 2025 profit expectations because people enrolled in health plans on the Obamacare exchanges were sicker than the company’s executives thought they would be. It’s a similar problem to other insurers, but with a twist.

Sure, Centene’s own exchange members are sicker than they predicted, but that’s not what could cost the company $1.8 billion. The problem is that everyone else’s exchange patients are sicker than Centene’s executives thought they would be.

Healing and Stealing readers know that Medicare adjusts its payments to private insurers based on “risk assessments” of each individual, allowing companies to boost their reimbursements by padding their members’ medical records. The federal government runs a similar program for Obamacare insurance, but “risk adjustment revenue transfer” for exchange insurers is a zero-sum game within the industry.

Insurers whose exchange patients are collectively healthier than other insurers’ populations have to send money to competitors who do a lousier job avoiding patients who actually need health care. Centene bailed on its profit predictions after reviewing claims from the actuarial firm Wakely for 22 of the 29 states where the company sells exchange insurance. Generally, Healing and Stealing reads corporate filings so you don’t have to, but it’s worth a minute to absorb Centene’s medico-financial jargon:

Based upon the Company's preliminary interpretation of the data and discussions with Wakely, the overall market growth in the 22 states is lower than expected and the implied aggregate market morbidity in those states is significantly higher than, and materially inconsistent with, the Company's assumptions for risk adjustment revenue transfer used in the preparation of its previous 2025 consolidated guidance.

The Company's preliminary analysis of the 22 states results in a reduction to its previous full year net risk adjustment revenue transfer expectation by a preliminary estimate of approximately $1.8 billion...

In the 22 states, fewer people are signing up for insurance through the exchanges than Centene expected, and the pool of patients in the exchanges is much sicker - “implied aggregate morbidity” - than they guessed. If those trends continue, they’ll have to give their competitors $1.8 billion and possibly more for the other 7 states. Centene hasn’t issued new profit projections - they’ve asked Wall Street to hang on until July 25, when they release their full 2nd quarter results.

Centene is a Fortune 500 companey - according to their 2024 SEC annual report, they collected $161.8 billion in revenue from 28.6 million members in 2024, turning a $3.3 billion profit (“net earnings”), a 27% increase in profits per share of the company’s stock in circulation. Like their peers, Centene earns those profits by skimming much more money from premiums than public insurance programs use for administration when they provide benefits directly instead of through private contractors.

What Centene calls its “health benefits ratio,” the percentage of premium dollars spent on actual health care, was 88.3% last year, meaning the company skimmed 11.7% off the top of its premiums for bureaucracy and profit, ten times the 1.1% that Medicare spent on administration in 2023 and more than twice the historic 5% average that Medicaid spends. Centene also told investors that their Medicaid plans are seeing “a step-up in medical cost trend” as well. Their 2nd quarter Medicaid “health benefits ratio” is likely to increase.

Centene’s announcement caused the price of its stock to drop by 40% overnight.

Centene plans to solve these problems with dramatically higher prices. Private insurers have to submit the premium prices they plan to offer people buying insurance on the exchanges to state insurance regulators in advance. A June 26 Georgetown University analysis of early filings for next year’s rates found “eye-popping” proposed increases, ranging “from 10% in Oregon to 24% in Rhode Island.” Those are becoming lowball figures - in its July 1 announcement, Centene assured investors that it is withdrawing its initial filings so it can propose even higher rates for 2026.

Molina: On July 7, Molina Healthcare announced its preliminary financial results for the second quarter of 2025 (April-June) while revising its own “guidance” to investors about how much profit to expect this year. Molina initially said it expected to see a slight increase in profits for 2025, up from $1.179 billion to $1.208 billion. Now company executives predict that they’ll produce slightly less than they hoped - not actually losing money, of course, just between $1 and $1.1 billion in profits vs. the $1.2 billion they originally expected.

You can tell Molina’s minor downward adjustment is a result of patients wanting to get the health care they paid the company for if you sift through the language crafted by the company’s skilled jargoneers. President and CEO Joseph Zubretsky told reporters that the slight decline in projected profits is a result of “a temporary dislocation between premium rates and medical cost trend which has recently accelerated.” The “dislocation” can be fixed by raising premiums, finding ways to cover healthier people and denying more care. It remains to be seen which of these traditional strategies Molina may adopt.

According to its SEC annual report, at the end of last year Molina had 5.5 million members across its Medicare, Medicaid and Obamacare exchange health plans (Molina doesn’t sell group plans to employers). Molina generated $40.7 billion in revenue - $38.6 billion of that from health insurance premiums - as the basis for that $1.2 billion in 2024 profits.

During the first quarter of this year, Molina skimmed 10.8% of its premiums for bureaucracy and profit (Like UnitedHealth, Molina calls it “medical care ratio”). The skim was down a bit from the first quarter of 2024, when they raked 11.5% off the top. However, they’re still lifting almost ten times as much as Medicare spends on administration.

Elevance: The company formerly known as Anthem hasn’t changed the amount of profit it expects to earn in 2025, but has warned investors that millions of patients actually want health care.

In its first quarter report to the SEC, Elevance said that what it calls its “benefit expense ratio”* increased from 85.6% to 86.4%. Elevance attributed the increase primarily to “Medicaid rates being inadequate to cover medical cost trends,” the unprofitable trend being people actually seeking the health care they paid for, or in the case of Medicaid, that federal and state governments have already paid for. Elevance did bring in more operating revenue in the first quarter of 2025 than the prior year, “primarily as a result of premium rate increases in our Health Benefits segment in recognition of medical cost trends.”

Reducing the company’s skim to a still-impressive 13.6% contributed to a small decline in quarterly profits when comparing January-March of this year to the same period in 2024 - from $2,246,000,000 to $2,184,000,000.

For three months.

Wall Street Hyperventilation: The fact that none of the five insurers we’ve looked at over the past two articles have, thus far at least, predicted anything remotely resembling actual losses this year illustrates two important features of the U.S. health care system.

First, Wall Street loathes actual health care. They’ve loved health insurance companies as they used political muscle to set up profitable reimbursement systems, including minimal regulation of care denials. However, as soon as those companies start paying for tmedical treatment, investors and the business press become enraged or despair that they’ll never make money on denying people health care again, or both. The Lever’s Katya Schwenk laid out investors’ message to insurers in a recent article: “Wall Street To Insurers: Keep Denying Care.” It’s worth reading as a companion to Healing and Stealing’s reporting.

Wall Street Journal reporter David Wainer captured the fear and fury last week, writing that “Health Insurers are Becoming Chronically Uninvestable.” That’s right, if you can only skim 9 or ten times what it costs the government to run a program instead of 11 or 12 times, and if you occasionally have to knock your profit expectations down a few percent, well, why would anyone buy stock in your company?

After all, the Fortune 500 came out last week, and only five health insurance corporations - United (3rd), CVS/Aetna (5th), Cigna (13th), Elevance (20th), and Centene (23rd) - are among the 25 largest publicly traded U.S. companies. Molina, with its paltry $41 billion in 2024 revenue, is a pipsqueak at number 111.

Wainer’s piece correctly points out that people wanting health care is a problem for insurers. He uses as an example the pandemic-era rules that allowed people to stay on Medicaid and the subsequent Great Medicaid Purge. Insurers, including Elevance, attribute some of the current rise in demand for health care to the fact that state governments purged Medicaid clients who were healthier than average. As Wainer puts it, during the pandemic, “many insurers were suddenly managing millions of low-cost enrollees…”.

Wainer ends that sentence with a reminder of an extraordinary fact - many Medicaid patients during the pandemic “didn’t even know they had insurance”. Aparently the insurers’ attempts to inform them of their benefits weren’t effective enough to encourage them to seek treatment. Now that more patients actually know they have coverage and are trying to get the care their premiums are supposed to cover, it’s making the industry “uninvestable.”

Too Big to Fail, Too Small to Succeed: The other key point is what a stunningly poor job the captains of American industry have done in running our health care system. At the risk of eyerolling repetition, the U.S. spends twice as much per person in our health care economy as other wealthy countries, but we see our doctors and visit our hospitals less often than the average of our more frugal peer nations. The sudden panic in finance circles over Americans wanting to be treated for medical conditions would be easily manageable in an efficient financing system.

U.S. capital has built health care finance into a collection of giant corporations. They wield enormous political power, but paradoxically are too small do to the job we’ve entrusted to them. By chopping coverage up into Medicare, Medicaid, exchange coverage, job-based coverage with differing rules for large and small employers, veterans and Indian health and then letting private insurers slice those categories into ever-smaller regional and local “markets,” policymakers have created a worst-of-all-worlds scenario.

Health insurance corporations are far too big to fail as an industry, so they are propped up by a series of legal reimbursement scams we’ve described elsewhere.

At the same time, they are far too small to succeed as an industry. Constantly shuttling patients from one type of insurance to another, and within that “market” from one company or “product” to another, focuses attention on profit-making enterprises’ guesses about who they will or won’t be covering a few months from now and how much caring for them will damage their shareholders, lenders and executives. As Healing and Stealing showed with a groundbreaking analysis of preventive care, health care financing functions best when a single pool of money covers a broad, stable population over a long time.

That’s why with trillions of dollars flowing into their coffers, the insurance industry still keeps begging the government to do their jobs for them, as with the absurd cost-raising dispute resolution process under the “No Surprises Act.” (According to Georgetown researchers, the latest data show providers are still winning 88% of the time on a high volume of cases. Nothing succeeds like failure in health care policy).

Centene’s July 1 announcement triggered a decline in stock prices across the industry. Elevance, which hasn’t changed its outlook, experienced a 12% drop the same day. Molina, with its own adjusted expectations yet to come, saw its shares drop 22%.

Investors’ nerves were jangled by more than Centene’s second quarter results. The announcement came as Congress was finishing the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act”, which includes significant changes to Medicaid, the exchanges and Medicare. There’s a little bad news for everyone in the bill. We’ll examine the policy changes and the politics surrounding them in detail over the next few weeks.

But neither the new law nor short-term declines in profitability merit the conclusion that private health insurers as a whole are no longer worth any investment. While failing to distribute health care fairly or efficiently, the insurance industry has shown remarkable skill in persuading legislators to allow them to loot the country. Despite worried headlines in the business media, that’s likely to continue.

*it’s darkly humorous watching the industry flee the phrase “medical loss ratio”, a bit of medical financialese they were proud to trumpet to investors, but it’s hard on Healing and Stealing’s word count to repeat the definition for each seperate euphemism.